A student’s journey from marine biologist to ocean mapper.

Ever since I can remember I’ve wanted to work in ocean sciences. From when I was a child splashing in the tidal pools of Big Sur, California and fantasizing about the creatures of the deep, this dream manifested as a marine biologist. From summer camps, to extracurricular classes, to countless hours spent under the blankets reading encyclopaedias on the marine world, everything I did was in pursuit of that goal.

Upon high school graduation, I packed my bags, said farewell to Dallas, Texas, and headed off to South Carolina. It was here at the College of Charleston that I would acquire my degree in marine biology.

Not once did I doubt my path. I was to be a marine biologist. Done. I immersed myself in my classes, took the most challenging courses I could find, and excelled. In detail I could explain the evolutionary history of invertebrates and name hundreds of fish species. The coast of Charleston was the classroom, and I attempted to absorb as much as possible.

Per the degree requirements, I enrolled in the undergraduate marine geology course led by Dr. Leslie Sautter. I was fascinated with the geologic processes underlying ocean formation as well as beach morphology.

When I handed in my final exam, Dr. Sautter asked me to join her on a research expedition where I would learn the skills needed for seafloor mapping. Still on the geology high, I accepted the position and set sail on the NOAA ship Ronald H. Brown for a two-week cruise mapping the northeast coast of the U.S. shelf edge.

I was captivated with seafloor mapping and the lifestyle of going to sea that it supported. The computer science and technical side was a new realm I had yet to explore with marine biology. I took to manipulating software and the immediate problem-solving one needs when participating with active operations. My sights were now set on working in the field of ocean mapping.

BEAMS

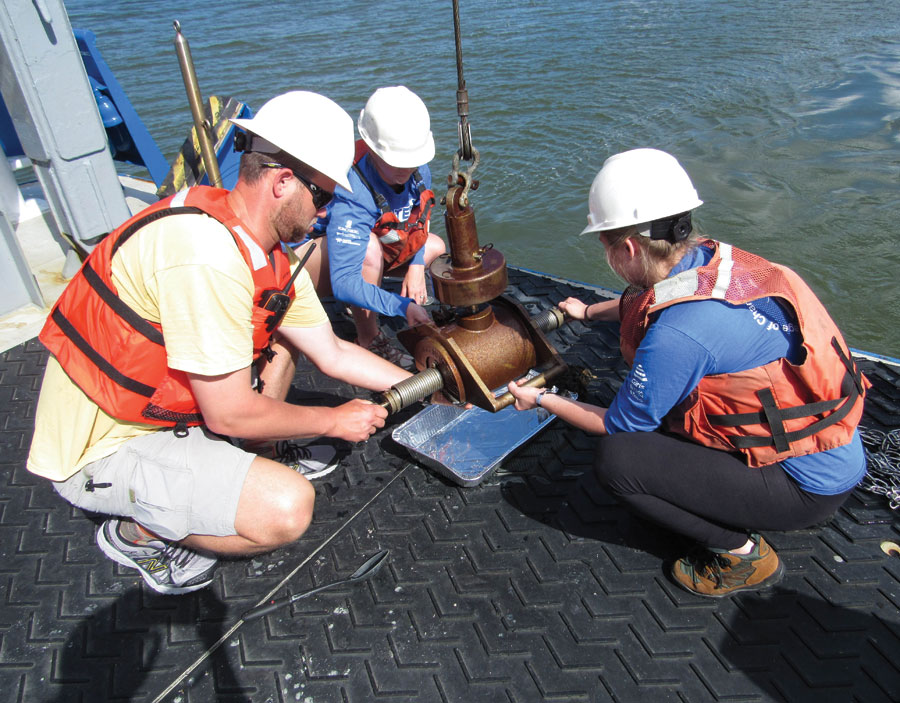

BEAMS students from the College of Charleston work on the R/V Savannah to retrieve sediment from a grab sampler in 2015.

I joined the BEnthic Acoustic Mapping and Survey (BEAMS) program at the College of Charleston. This program, which began in 2006, has trained and educated 114 undergraduate students in seafloor mapping. Students learn techniques for seafloor mapping, including marine survey instrumentation, software manipulation, and scientific interpretation.

More than half of the graduates of BEAMS are active in the workforce, with 40% of those students being female. Forty-two undergraduate students have participated in 66 research expeditions, representing the College of Charleston across the globe.

The success rate of the BEAMS students is a testament to the program and those who lead it: Leslie Sautter (College of Charleston), Paul Cooper (CARIS USA), and Miles Logsden (University of Washington). The network created via this program is one of the most valuable assets I received from my time at the College of Charleston.

Since that first cruise on the Ron Brown in 2009, I have had the privilege to participate in nine research expeditions, mapping areas from the continental shelf of Antarctica to crossing the Marianas Trench, to mapping seamounts across the Atlantic Ocean. I received a contracting position with the United States Geological Survey participating in a Submarine Geohazards research project. In September, I will pursue a Master’s in earth sciences with a concentration in ocean mapping from the University of New Hampshire. Other graduates of the BEAMS program have gone on to hold well-sought-out positions.

At Drake Passage

In 2011, midway through pursuing my Bachelor’s in marine biology, my geology professor received a request for a student to participate in a 36-day research expedition on board the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer in the Drake Passage. The stipulations were that the student needed to be both experienced with seafloor mapping and able to handle rough seas.

Shannon (left) assists a marine technician with retrieval of the CTD on board the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer.

Because I’d already participated in four research expeditions, one transiting from Indonesia to Hawaii, it was decided that I was the student for the job. I was sponsored by the software company, CARIS, to teach CARIS to the on-board technician, as this would be the first cruise with the new software. I prepared myself to venture into the Antarctic as a mapping watch lead.

This cruise solidified my desire to pursue a career in seafloor mapping. It was the first expedition on which I was able to work autonomously and take on more challenging roles than that of an intern. The work was difficult, engaging, and completely rewarding. The 12-hour work day went quickly as it was packed with constant learning and new problems to solve.

Not only did I participate with mapping operations, but I was also able to aid with other scientific operations such as trawling, dredging, coring, and sorting the subsequent samples. I was completely in my element.

As a bonus to the rewarding work, I was able to experience transiting through the Bransfield Strait, a passage between Antarctica and the coastal islands. Never before had I seen such natural beauty. The ship was surround by ice floats occupied by massive fur seals or Antarctic sea birds.

As we broke through the ice, gazing upon Antarctica reflecting the colors of the setting sun, I realized that I was able to experience this because of seafloor mapping. It was at that moment I knew I was to be an ocean mapper.

As a marine biologist, I was lost in the crowd, unable to differentiate myself. The jobs were few and far between. Through the BEAMS program, I was able to gain the skills, experience, and network to be viable in the field of ocean mapping. Looking forward, I will continue to pursue a career in habitat mapping, which fuses my backgrounds of marine biology, marine geology, and mapping technologies, as well as promotes global efforts to utilize ships of opportunity to effectively map the world’s oceans with sonar technology.

My path forever changed on the bow of the Ron Brown and I will never look back.