A Case for Big Blue Data

Note: xyHt is honored to host insights from Dr. Dawn Wright and Captain (ret.) Rafael Ponce, two distinguished scientists in the fields of hydrography, marine surveying, and oceanography. Parts one and two of our interview appeared in the September and November 2015 print issues of xyHt.

xyHt: Terrestrially, a boom is occurring in big geo-data with remote sensing, airborne and mobile scanning, lidar bathymetry, 3D multibeam, satellite imagery, and radar interferometry. Is there a similar boom happening for the marine environments? Also, are there marine-measurement capabilities or technologies that you would like to see developed (or enhanced, if they already exist)?

Dawn Wright

I do think there is a boom of sorts in the marine environment. Space-borne and airborne platforms can be great, but again, they can see only so far down in the water, and even less if the water is not clear.

Although a new bathymetric satellite alti- meter mission could significantly improve our ability to map synoptically over large regions of the ocean [see Smith and Sandwell, 2004], I believe that ships on the surface or vehicles down in the water equipped with echosounders remain the best solution for detailed mapping and measurement.

It will also be exciting to see how one might generate energy where you really want to do your science.

For instance, I think one of the biggest developments for marine environments has been the emergence of underwater gliders that operate in the ocean or near the coast, autonomously, collecting all kinds of wonderful data.

They can surface and send that data to shore. They can also ping off devices that are on the bottom, thereby picking up that data and sending it to shore. They are cheap, so it’s relatively easy to build them, put them in the water, and keep them in the water (although keeping them in the water for extended periods is a challenge because of batteries and so forth).

Overall, the development and emergence of autonomous technologies such as these is really exciting and important.

It will also be exciting to see how one might generate energy where you really want to do your science. This will be an exciting “new” problem to solve: moving electrical energy from where it is generated to where it is needed.

What are the possibilities for geothermal power on the seafloor or wave-power generation on the sea surface for instruments deployed year-round collecting data? I was at a National Academy of Sciences workshop a few years ago where it was predicted that, by 2030, we’ll see a combination of systems collecting data in the ocean: some mobile, some fixed, some generating their own power, an increasing specialization of robots (such as these gliders), and the ability of robots to function cooperatively.

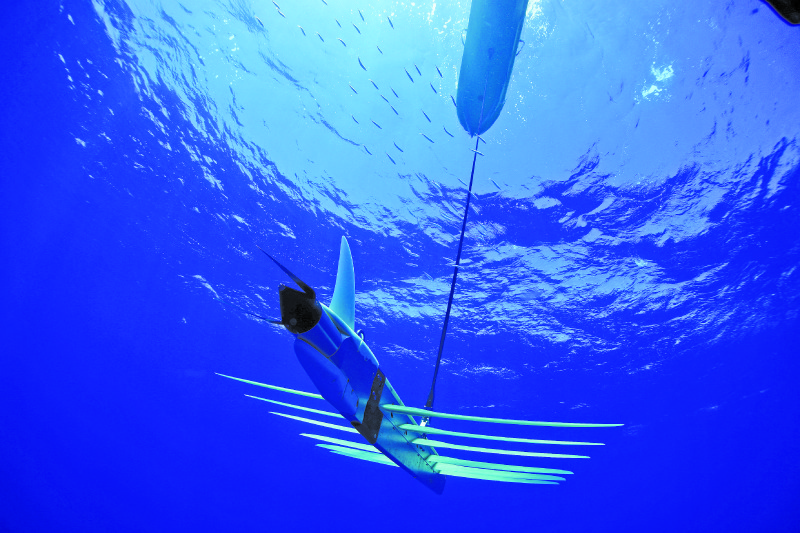

Cutlines: Vast, uncharted areas of our oceans are now being mapped and studied for the first time with new technologies and innovation. In addition to satellite-derived bathymetry, fleets of autonomous underwater vehicles like the Seaglider, below, and the Deepglider, at right (both from the Seaglider Fabrication Center at the School of Oceanography, University of Washington) silently glide for thousands of miles in a single deployment. These compact robots use minimal power to subtly adjust buoyancy and sea wings to “glide” with and across currents, gathering data and surfacing only periodically to report back via satellite communications.

Rafael Ponce

Yes, there are many parallels between the land and the sea. Big data is not exclusive of land; since the time of the start of multibeam systems back in the 1980s, bathymetric data-collection experienced a boom.

I remember the days when we used to analyze sounding by sounding, [which is] not possible anymore with multibeam. These multibeam systems have evolved tremendously, and thankfully there are semi-automated methods based on uncertainties (such as CUBE: Combined Uncertainty Bathymetry Estimator) that allow hydrographers to post-process collected bathymetry fast and reliably.

Now with SDB [satellite-derived bathymetry] and marine lidar in the mix, the amount of bathymetry that an organization has to potentially manage can be huge. And here I’m thinking only of bathymetry, not to mention all the ancillary data that is collected, in addition to bathymetry, for post-processing (tides, sound velocity profiles, sediment classification, etc.). [Considering this plus] all other ocean data that is collected for other purposes, using a myriad of platforms and sensors, and we have a case for “Big Blue Data.”

I would like to see ellipsoidally referenced hydrographic surveying become more reliable

In terms of bathymetry, I think the new SDB technology brings new opportunities to adequately survey shallow waters at reasonable prices and in record times (much faster than acoustic and marine lidar surveys). I would like to see this technology to the point where you can trust SDB depth as much as a multbeam (or acoustic) depth.

I would also like to see crowd-sourced bathymetry to evolve and come up with reliable data for the large part of the ocean floor (at least for the main shipping routes).

Another important area that I think is advancing significantly has to do with vertical datums: I would like to see ellipsoidally referenced hydrographic surveying become more reliable by improving high-accuracy GNSS processing techniques in order to use the vertical component effectively. This would help a lot where there is no tidal datum available or it is unreliable or old.

On this subject, Esri is developing capabilities in ArcMap to make vertical datum transformations reliably using mosaic datasets and the ArcGIS 3D Analyst toolset in combination with the ArcGIS for Maritime Bathymetry solution. This development was presented at the Canadian Hydrographic Conference in 2014 and as a paper at the Shallow Survey Conference, addressing the issue of accurate management of cadastral boundaries for aquatic lands at three tidal datums.

I also think that the new ocean glider technology will make ocean data-collection more pervasive and achievable in the near future. The ArcGIS platform can take and allow a better understanding of our world’s oceans, from which we can predict (and why not) modify our future.