We continue this series on treasure hunting with geospatial tools by taking a peek at what the future may hold for seekers of undersea hidden treasure.

The tale of Mel Fisher and his hunt for the “Nuestra Senora de Atocha” illustrates the difficulties of undersea treasure  hunting. The Atocha was the most famous ship of a fleet of Spanish ships that sank in 1622 off the Florida Keys during a hurricane. It was carrying copper, silver, gold, tobacco, gems, jewels, and indigo from Spanish ports at Cartagena and Porto Bello in New Granada (what is now Colombia and Panama, respectively) and Havana, bound for Spain.

hunting. The Atocha was the most famous ship of a fleet of Spanish ships that sank in 1622 off the Florida Keys during a hurricane. It was carrying copper, silver, gold, tobacco, gems, jewels, and indigo from Spanish ports at Cartagena and Porto Bello in New Granada (what is now Colombia and Panama, respectively) and Havana, bound for Spain.

The renowned treasure hunter Mel Fisher searched for the Atocha for sixteen and a half years, finally discovering the wreck in July 1985. The worth of this find is estimated at $450 million. A short list of Fisher’s find includes 40 tons of gold and silver, 114,000 of the Spanish silver coins known as “pieces of eight,” gold coins, Colombian emeralds, gold and silver artifacts, and 1,000 silver ingots. There are believed to still be 300 silver bars and other treasure still undiscovered.

Why it took Fisher and his team more than 16 years to find this treasure leads us to how geospatial technology could make this process faster, safer, and more profitable. The first step in finding the general area of a treasure is one of meticulous research into old maritime records, in this case Spanish archives. Once the basic location is discovered, it becomes a grid search, making it an ideal application for unmanned platforms. Can you imagine the patience and endurance it took for Fisher’s team, the Salvors, to manually scuba dive for 16+ years in the uncertain search for this treasure? Marine salvage is dangerous as well; Fisher’s oldest son Dirk, his wife Angel, and diver Rick Gage died after their boat sank during this operation. It is axiomatic that unmanned systems are ideal for task that are “dull, dangerous, and difficult”—let’s add dark and deep to that.

In the last issue, we talked of the role that ROVs play in the search for underwater treasure. Let’s step into the future to look at how autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) could help.

On the low end is the VideoRay CoPilot, an autonomous upgrade to the VideoRay ROV. Two options are available: the Sonar CoPilot and the RI (Reacquire Identify) CoPilot. Sonar CoPilot uses Teledyne’s BlueView P900 series imaging sonar to locate, identify, and fly to targets. RI CoPilot relies on the Teledyne RDI Doppler Velocity Log (DVL) to provide real-time GPS position data. Each package provides autonomous control capabilities for the VideoRay Pro 4 system.

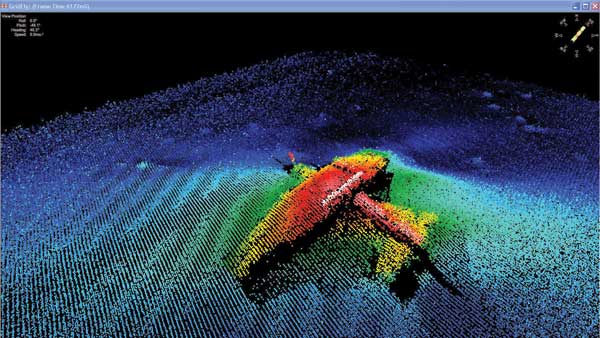

On the upper end is Teledyne’s Gavia Offshore Surveyor. This AUV is capable of performing side scan, bathymetry, and sub-bottom surveys at depths of up to 1000 meters (3280 feet).

On the upper end is Teledyne’s Gavia Offshore Surveyor. This AUV is capable of performing side scan, bathymetry, and sub-bottom surveys at depths of up to 1000 meters (3280 feet).

Neither of these platforms is for the budget-minded. However, the cost of an autonomous craft must be weighed against three other factors.

Reward: finding a treasure ship could yield a multi-million dollar payday (the Atocha is estimated at $450 million).

Risk: the chance of serious injury or death to a crew member can be eliminated with an AUV.

Cost-savings: the search for the Atocha took 16 years; imagine paying professional divers, support crew, and other associated costs like fuel, food, etc. for that many years. With these factors in mind, even a million-dollar AUV seems cheap.

In part two, we take to the skies to see what UAS can bring to the field of treasure hunting.