A community gathers for the dedication of Dave LaMure Jr.’s sculpture, “A Vision of Tomorrow,” honoring pioneering surveyor John E. Hayes.

Updated: Nov 11, 2018. Audio presentation added at the end of the article.

The statue of Hayes was unveiled on July 6, 2018, at a dedication event for the sculpture and new city of Twin Falls Commons. Photo: Schrock.

“This has changed my life,” said Dave LaMure, Jr. “It has touched me here,” he added, gesturing to his heart.

LaMure speaks a lot about heart, literally, figuratively, metaphorically, and spiritually. His personal journey led to the creation of this stunning sculpture, dedicated in July of 2018, inspired by the history of his home region and a little-known historical figure: surveyor John E. Hayes. The project served to strengthen feelings about home, heart, and community.

The story of John Hayes and the path that lead to the creation of this artwork is of the transformation of a region through cooperative efforts and exemplary feats of land surveying using the relatively primitive instruments of that era. And, quite literally as well, this artwork immortalizes a singular moment in time: the establishment of the central point—the heart of a new community.

“A bronze man still can tell stories his own way”—“Saturday in the Park” by Chicago (Lamm)

The Magic Valley

A broad and relatively flat region of the Snake River Plain called the Magic Valley, in South Central Idaho, lies between a mountain range to the north (famed for skiing) and a lower range to the south. When we think of the word “magic” we think of the amazing, the unbelievable, and the inexplicable; this story of Magic Valley is one of real, practical magic.

Magic Valley in South Central Idaho. The wide swath of green in the distance beyond the sagebrush of this otherwise arid region along the Snake River was transformed by the Twin Falls Canal project into some of the most productive agricultural lands in the United States. Photo: L. Zamora.

As you drive along the interstate or fly over, you see the muted colors of the arid surrounding valley suddenly give way to a sea of green: the agricultural lands fed by various irrigation systems. The transformation of this arid valley—that many had written off as uninhabitable—into some of the most productive farm country in the United States is nothing short of magic.

And, as these events occurred relatively recently with substantial written and photographic records, we see that this magic came from the imagination and hands of exceptionally skilled engineers, surveyors, forward-thinking investors, and local visionaries.

Success Inspires a Bold Plan

The Snake River cuts deep gorges in the plain of basalt and volcanic soils. The waters of the Snake River represent the lifeblood that would turn this wasteland into productive farmland were it not so inaccessible. Early settlers in the late 19th century did have modest success farming on the wider areas of the lower gorge and where the gorge was shallow enough to allow simple water wheels to irrigate the surrounding plains. But, for the most part, these were isolated endeavors.

One successful farmer and entrepreneur, Ira Burton Perrine, established a ranch in the lower Snake River Gorge near present-day Twin Falls, not far from a large arch bridge now bearing his name, connecting Twin Falls to the nearby interstate highway. His ranch, ferry, and eventually bridges were central to the region. The volcanic soil and relentlessly sunny growing seasons bore such fertility that Perrine won international prizes for his produce. Perrine recognized the potential of the region, and while he joined others in promoting the idea of a regional irrigation system, he was one of the most persistent in lobbying efforts.

Prominent people involved in this grand project appear as namesakes for towns, bridges, dams, and other features: the towns of Buhl and Kimberly were named for industrialist investors, Milner Dam for the investor who would lead much of the construction, the town of Filer for an investor/engineer/manager, the town of Hansen, and others. And, of course, several items were named for I.B. Perrine.

One of Hayes own photographs: along the canal with one of the new “automobiles” crossing one of the hundreds of bridges built over the network of canals.

One key figure in the massive irrigation project that would transform the valley and region does not appear as the namesake of any places, roads, or structures: surveyor John E. Hayes. His name might have gone unknown to all but some local history buffs were it not for a compelling piece of journalistic research: a book with Hayes on the cover.

From the time of the earliest settlers, the land of what would become the Magic Valley had already been transformed by the hand and activities of humankind. The valley was once a sea of Buffalo Grass that had been stripped away by successive cattle drives, leading to erosion from the relentless winds. What would take its place were a few species that could survive in these conditions, primarily sagebrush, or Wormwood.

The iconic photo of Hayes, on the first day of the survey laying out the City of Twin Falls in 1904, appeared on the cover of a book a century later, inspiring the community and artist Dave LaMure Jr. Photo courtesy of the Hayes Family.

A Forest of Wormwood is a book by journalist Neils Sparre Nokkentved that’s a good read on many levels, not just for local history buffs but also as a case study of one of the most impactful projects of its era and one that many said could not be done: the largest privately funded irrigation project in the United States.

Nokkentved, a noted northwest journalist, had been writing about policy and environmental and natural-resource issues for newspapers in Idaho, Washington, and Utah for over 20 years. His book includes details about the work of John Hayes, especially his role in choosing and surveying the site of the city of Twin Falls, which would become the largest city in and the heart of the Magic Valley.

The Canal Company

A group of local visionaries and investors from “back east” formed a plan to irrigate 200,000 or more acres of this potentially valuable land under the auspices of the 1894 Carey Act. This U.S. Federal act sought to encourage and support private firms in constructing irrigations systems, with the incentive that if successful they could profit from them.

While many potential investors had become wary of Carey Act projects (as some of the first such projects elsewhere had mixed success), Perrine and others were persuasive and made a solid proposal. What would later become the Twin Falls Canal Company was formed, and it still prospers today. It is a fascinating story of engineering, surveying, and the pioneering spirit of the American Northwest. Another good read on the subject is the book commissioned by the canal company: A History of the Twin Falls Canal Company – 1905-2005 by J. Howard Moon and Russel M. Tremayne.

Early surveys by John Frederick Hansen and others gave the general lay of the land, topography, and most important the range of vertical relief that could enable a gravity irrigation system. Water and gravity are the magic behind passive irrigation systems, but only if you have accurate surveys, especially in a relatively flat region.

The mouth of the main canal at Milner Dam was the starting point for Hayes survey of a network that would encompass thousands of miles of canals and laterals. Photo: Schrock.

The key to the proposed irrigation system would be a diversion dam, upstream some 20 miles east of the Blue Lakes Ranch, forming small lakes and feeding two main canals that would reach to areas south of present-day Twin Falls and far beyond. Eventually, this network of canals would encompass thousands of miles of laterals and minor structures. There is a Northside Canal Company (NCC) that gets water from the same Milner Dam as the Twin Falls Canal Co. The NCC extends towards the city of Jerome.

Fire would force a sudden turn in the planning, design, and construction. Surveyors know (and some learn the hard way) that you need to make multiple copies of survey records. A fire in an office in Salt Lake City that housed project survey records prompted the canal partners to commission new surveys, and this brought a remarkable young fellow to take on the task.

John Edward Hayes

Born in 1877 in Kirkwood, Illinois, John Hayes was an exceptionally bright young fellow. He had been accepted for engineering studies at the University of Illinois but also played professional baseball in St. Louis, as a catcher in the days of no backstop and often no gloves. His plans and funds for college fell victim to the financial panic of 1893, also known for the collapse of the silver trade. Coincidentally, the same crash scuttled an earlier plan for canals in the Magic Valley.

Through his brother in law, Hayes secured a job as a chainman on a survey crew in the Cripple Creek mining district of Colorado—at the age of 16. Hayes learned rapidly, taking on increasingly difficult duties, and he joined in adventurous surveying across the American West.

Hayes worked on original U.S. Public Lands Surveys, including what is now part of Glacier National Park in Montana and the densely forested coastal regions of Oregon. As his grandson, Dr. Robert K. Maddock Jr., relates in the telling of his grandfather’s surveying stories, on surveying in the Oregon forests, “It was so dark in the middle of the forest, even at midday, grandfather had to hold up a lantern to see the stadia marks.”

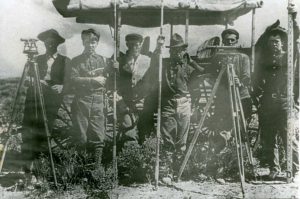

A canal survey crew near Milner Dam circa 1903. Credit: Twin Falls Canal Company

A synopsis of professional record (much like a resume) published by Hayes covering the years of 1893 to the mid-1920s seems almost hard to believe. But in preparation for the dedication of the statue, the project organizers asked present-day surveyors in each place noted on the synopsis to vet the entries. And sure enough, there are paper trails confirming Hayes’ participation in each of these surveys. (Read his professional record at: goo.gl/djTnyo.) He was a remarkable and prolific surveyor by any measure. Although he had no formal education after high school, Colorado granted Hayes his engineering license based on his vast experience. A recently located survey field book was marked with his Colorado professional stamp: Hayes’ license number was “P.E. #18”!

Hayes had previous experience with a canal in Oregon so was hired on for the Idaho project. He initially worked as the instrument-man on a large survey crew. While visiting John Hansen in Rock Creek (a staging area for the surveys), he got a chance to look over some of the early survey maps Hansen had prepared years before, he met Hansen’s daughter, Anna, who would feature prominently in his future.

Surveying the Canals

What these surveyors accomplished with the instruments of the time might be hard for most surveyors to complete even with all of today’s high-tech instruments. The topographic maps of the day were rough at best, and a surveyor would have to make decisions in the field to ensure this gravity system would work.

While the diversion dam was being constructed upstream, work began on the canals with the hope that they would be ready when the dam was complete.

The beginning of the 20th century saw other dramatic changes. Where there is flowing water, electricity can be generated, and several small hydro generators fed electric heavy equipment for the dam construction, and parts of the canals (though horse-drawn drag buckets and a small army of workers did a lion’s share of canal excavation).

Hayes’ original field notes and the transit depicted in the sculpture, and as seen in the iconic photograph of the initial survey of the city of Twin Falls (from the Twin Falls Canal Company collection). Photo: Schrock.

To keep the canals as high as possible on the terrain to provide enough elevation differential to feed as many lateral canals as possible, there were tight tolerances with little room for error in surveying. Instruments like long-telescoped K&E spirit levels transferred elevation by three-wire methods and were used for ranging by stadia.

Milner Dam is a relatively short diversion dam; it raises the waters of the Snake River only 39 feet. The shallow drop in surface elevation from the dam to the downstream fields to be irrigated called for a main canal design that allowed for barely 12 inches of drop per mile.

Hayes was up to the challenge and was relied upon more and more for his expertise in judging the lay of the land and for adjusting the canal route for optimal flow. The bulk of the work was perhaps tedious mile after mile of leveling for the canals, but there were a few interesting challenges along the way (besides the heat, cold, dust, rattlesnakes, and often boredom).

The Rock Creek gulch had to be crossed, and rather than building a costly aqueduct, the company opted for a siphon. Two 90-inch pipes are still in operation, though now encased in concrete.

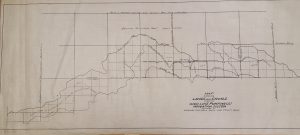

One of many maps produced from Hayes survey notes: he would draft many himself. From the Twin Falls Canal Company archives.

Hayes made another key recommendation: to avoid very long lateral canals it would be best to have two main canals running west from the dam. This idea resulted in a second canal, the Low Line being built to the south of the original High Line canal.

A New City

Not many surveyors in this day and age get the honor of laying out a new city, but Hayes laid out eight small cities and towns in the Magic Valley. Of the eight he laid out, the story of the layout of Twin Falls garners the most interest, not just because the city is the largest in the valley but also for an interesting “twist” (no pun intended) Hayes added to the city plat.

The area of the canal system needed a major city: a hub for commerce and a heart of the community. Hayes was given a simple set of criteria: a relatively flat area, central to the region. He found a prime location on the flat plain of sagebrush, set back from the top of a 500-foot cliff rising from the Snake River.

Aerial and satellite images show the distinctive skew of the central part of Twin Falls, a deliberate feature added by Hayes to the original city plat. Image: Bing Maps.

Hayes knew that working a city plat through bureaucratic hoops for a Section 16 (typically reserved in the Public Lands Survey System to benefit schools) would be much easier than for other lands. In 1903 he set a stake and white flag near one corner of Section 16 of Township 10 South, Range 17 East, Boise Meridian. Hayes returned a year later in April 1904 to lay out the town and added an interesting “twist” to the city plat.

Typically, new cities of the day were laid out with streets running north-south and east-west. So why did Hayes skew the streets of Twin Falls by 45 degrees? Some say it was so that all four sides of each house would get sun each day in winter; others say it was in consideration of natural drainage.

Maddock Jr. said, “He wanted to keep the sun out of the eyes of wagon drivers, heading east and west.”

Hayes had a famous sense of humor and would sometimes offer alternate wild explanations for fun. Though we can be confident in his grandson’s explanation, an air of mystery lingers.

The Photograph

The iconic photo of Hayes inspired another local artist Leon Smith with his oil on canvas painting now in a private collection. Courtesy of Art and Bonnie Hoag.

Hayes returned to Section 16 in April of 1904 to lay out the town. He was working at the behest of a city establishment committee that had chosen the name, “Twin Falls,” after a pair of falls miles upstream. There was already a town named Shoshone, so they could not name it after the iconic and massive Shoshone Falls closer to town.

Among his many pursuits, Hayes was an accomplished amateur photographer. While we could not verify that the photo on the right was taken with his own camera, someone evidently had the foresight to capture this historic moment in the history of the region, snapping a photo of Hayes looking through his surveyor’s transit near the center of Section 16. This initial point was at the intersection of what is now Main and Shoshone Streets, the very heart of Twin Falls and the Magic Valley

Courtship and the Courthouse

On May 12, 1904, upon completion of the survey for the new city, Hayes jumped on his horse and set off on the nearly 60-mile trek to the county seat in Albion to file the new plat. And to visit the young lady working at the county office, Anna Hansen, who was noteworthy in her own right. They would later marry and raise a family.

Local resident James Varley, since deceased, wrote a touching article about John and Anna Hayes, published in a local paper in the 1970s. Varley’s article provides us with details about Anna Hansen Hayes, quite accomplished considering the lack of opportunities for women at the time. As she was exceptionally bright, no one was surprised she would bond with Hayes. Anna graduated from The Normal School (a distinguished college in Albion) and soon became an assistant professor. She served on numerous foundations and was consultant to the newly formed PTA of Japan during the post-war reconstruction. A prolific writer, Anna authored books of poetry and two books on life in the Rock Creek area. Hayes was still busy with the canal project though 1909, but the couple found time to get married on Christmas day in 1905 and build a new house in Twin Falls not far from the original point.

Shoshone Falls, on the Snake River near Twin Falls, Idaho, is known as the “Niagara of the West.” In 1905 when the gates of Milner Dam were closed to fill the new canals, the falls temporarily ran dry.

There is an inscription on a plaque at Milner dam that describes the day the water flowed:

On March 1st, 1905, Frank Buhl gave a ceremonial pull on the wheel on a winch and the gates of the Milner Dam were closed, and the gates to a thousand miles of canal and laterals were opened, and the Snake River was diverted. And that night, Shoshone Falls went dry as the water rushed across the desert far above, and Perrine’s dream was realized, and [over 200,000] acres of desert were transformed.

The Twin Falls canal company was born, and it brought in farmers from all over the country. John and Anna continued to reside in Twin Falls while Hayes worked on several other large projects in Idaho. The couple would amass a private library in their home and were involved deeply in the community. While they did move to Salt Lake City for a spell, they returned to Twin Falls, where Hayes would serve as manager of the canal company for short while, as city engineer then county surveyor. He also participated in numerous other ambitious surveying and engineering projects.

Hayes was determined to help the war effort during the Second World War, but he was aware that he was by then too old to serve in traditional roles. His grandchildren say that he asked the War Department what he could do to support the war effort. He was tasked with laying out Wendover Field in Idaho, an Army Air Corps base with a particularly long runway. The field was used to train B-17 and B24 bomber pilots, then B-29s, including those that would carry the first nuclear payloads at the war’s conclusion. The field is now Wendover Airport.

Several of the Hayes grandchildren attended the statue dedication; they related experiences with their grandfather, including working a surveyor’s rod and “pulling the tape through the sagebrush” on some of their grandfather’s surveys. Their memories do not paint Hayes as a “task master” style survey party chief but instead as one who teaches but would appropriately press his crew to keep up a good pace.

Two of his grandchildren, Maddock Jr. and namesake John Edwin Hayes (now the vicar of Cancun, Mexico) spent time as military surveyors, although more in a forward fire capacity than in conventional land surveying. Grandson John Edwin Hayes notes that he once held the role of chief surveyor for the Navy in the Pacific region but had only one surveying instrument, a different kind of surveying than that of his grandfather.

John Hayes died in 1962 at the age of 84. His was an accomplished life, not just in surveying but in everything he and Anna pursued. Few really knew of the whole of his and Anna’s fascinating story, but that famous photo would change that more than five decades after Hayes’ passing.

Maquettes

I wish it were possible to list and acknowledge everyone who supported the development of the sculptural tribute to John E. Hayes. The list would be long—the agencies, boosters, foundations, and trusts. There are so many stories of individual and group efforts that made this happen.

At the luncheon at the local country club the day of the unveiling, I met many of the people involved as well as four of Hayes’ grandsons and their families. Many gave speeches on Hayes, local history, and the story of this public art project. But most acknowledged that there were three key figures who sparked the idea: the sculptor Dave LaMure, Curtis Eaton, and Paul Smith.

Smith and Eaton are a retired attorney and a retired judge who have been friends for many years and who were partners of sorts on the Hayes’ sculpture project for about three years. Smith had also started the Twin Falls Historic Preservation non-profit.

Six years ago, Smith had been asked by the Twin Falls Canal Company to come up with ideas to boost the image of the company and foster a sense of community among the shareholders. While the acreage served had not shrunk, the numbers of individual shareholders had through farm consolidations. Someone brought a copy of Nokkentved’s book to his office and said, “You have to read this.” He and Eaton did, as well as others involved in this art and community project, and they were impressed by the story. But their attention was also drawn to the photograph of the surveyor on the cover. “We have to do something with this,” they concluded.

This photograph from the collection of the Hayes family had inspired others. Leon Smith, a noted local artist who has painted award-winning scenes celebrating the pioneer spirit of the region, produced an oil painting of the iconic scene. Leon Smith’s painting is now in the private collection of Art and Bonnie Hoag, local art boosters who also became involved in the sculpture project.

Artist Dave LaMure Jr. first sculpted in clay to cast 18″ tall statuettes (maquettes). then the larger-than-life Hayes in clay to create molds for the the cast bronze statue.

Curtis Eaton and Paul Smith began thinking about sculpture. In jest, they referred to Hayes and his role, so central to the establishment of the town, as the “belly button” of Twin Falls. That term served in an unexpected way to help inspire the sculptor Dave LaMure, Jr. as he worked on the first mock-ups and then the full-sized statue.

Tapping the talents of this local artist, they first sought a small mock-up, a statuette, more properly called a “maquette.” LaMure studied the photo and worked in clay to form the maquette, later to be cast in bronze. He kept Smith and Eaton’s belly button comment in mind as he worked to inscribe the form of Hayes in a circle.

LaMure said, “I took a plumb bob and held it up to his eye, envisioning the future town. Then I held it up to his belly button. Between the two marks on the surface below I picked the midpoint for the center of the circle–directly below his heart.” In keeping with one of his central themes, LaMure noted that midway between one’s eyes and belly button area (center) is the heart.

LaMure faced challenges in creating the three-dimensional visage of Hayes and the event in the photograph as there was only one photo from one vantage point to work with. In balancing fidelity to history and conveying the spirit and emotion of the event, LaMure has succeeded in a striking manner.

He consulted with Louis Zamora of the Twin Falls Canal Company and local surveyors like Tom Ruby, Bert Nowak, and Dale Riedesel to make sure that the details of the surveying equipment of that era were correct.

Ruby pointed out a missing tangent screw on the back of the sculpted transit, which LaMure later added and called the “Ruby key.” Rumor has it that “Ruby” is inscribed on the top of that tangent screw on the full-sized sculpture, out of view (but I was not going to climb up the stature to verify).

Only a few notable changes from the original photograph were made. The artistic liberties are that the transit in the photograph had an enclosed vertical circle (very practical for the windy, dusty conditions), but an open vertical circle worked so much better for the finished sculpture. LaMure looked at the hand positions in the photograph and found that their positions caught in that moment did not help convey the broader story he envisioned for the art to tell. LaMure wanted to emphasize the type of energy Hayes would have been putting into his thoughts of the future, so he extended one arm slightly and placed an open palm facing forward to that future.

These 18” tall bronze maquettes of Hayes and the historic moment caused a lot of excitement. They sold 14 of them (even at $5,800 each). Visions of a full-sized sculpture, as a public art installation in the city of Twin Falls, began to take shape.

Unveiling

Twin Falls is undergoing a renaissance with large international businesses locating there (e.g. Chobani) and local agriculture doing well. There has been a lot of recent activity among the circles of urban renewal agencies and organizations and Magic Valley arts boosters. The city had been planning a “commons,” a central gathering place for the city with a stage for public performances, events, and festivals—and there would also be a fountain for kids to play in during summer months. Among the supporters were the Bowers and Keveran Foundations, the Twin Falls Urban Renewal Agency, and city officials: all of these essential in the realization of the commons and sculpture projects.

The Commons was built at the corner of Main and Hansen Streets, only a block from Hayes’ original point (that intersection would be impractical for the sculpture). Plans were made to set LaMure’s “A Vision of Tomorrow” art in the southernmost corner. In another corner is an original stone set by Hayes in 1904, placed on a pedestal with an explanatory plaque. The idea was to unveil the statue at the official opening of the Commons in July of 2018.

LaMure proceeded with the full-sized (1.32x scale) statue. He sculpted sections in clay, then cast these in plaster, then recast as forms for the foundry. LaMure had previously done work with that famed foundry in Joseph, Oregon.

LaMure adds many facets to his art and finds so many connections among all of the elements that go into them. He noted that the founding event in Twin Falls was in 1904, the year Chief Joseph, inspirational historic figure in the Northwest and namesake of the town where the foundry resides, passed away (in Joseph, Oregon).

One of the original town site stones has been installed on a pedestal on the opposite side of the City Commons , on line with the transit in the sculpture. Photo: Dave LaMure.

The finished sculpture stands over seven feet high and is on a base incorporating many of the wild creatures of the region from that era. Surveyors will note that the plumb bob is centered precisely over the mark in the set stone. There is something ethereal about the sheen of the bronze in this statue, almost like the clear Idaho afternoon sun is always glowing on Hayes. Set on a stained concrete base pedestal, surrounded by local basalt rock, the full installation stands over 10 feet tall.

On the day of the dedications, July 6, 2018, of both the Twin Falls Commons and unveiling of the statue, hundreds of residents filled this new park. At the podium were speeches by the mayor, a state legislator, the urban renewal agency, arts boosters, and others. These speeches all touched on themes in common with LaMure’s heartfelt speech his message about home, heart, and the vision of tomorrow that the eye of Hayes, peering through his surveyor’s scope, had on that day in 1904.

LaMure quoted poet Maya Angelou: “If one is lucky, a solitary fantasy can totally transform one million realities.”

To kick off the unveiling, professional BASE jumper (also from the region) Miles Daisher parachuted over the town and landed on Hansen Street next to the sculpture. As the shrouds were removed, the enthusiasm of the crowd evidenced the full impact of just how “striking yet inviting” the statue is.

The enthusiasm was not limited to the crowd at hand. I tracked photos posted that same day on social media and saw, of course, great interest among surveyors, engineers, and history buffs, but also tens of thousands of other views across the region, state, and nation and have seen comments posted from overseas. We at xyHt posted live videos and images, noting that an article was in the works. We’ve since been deluged with inquiries about when it will be published and suggestions by surveyors proposing emulating this type of public art initiative in their own communities. It is heartening to see that a statue of a local hero can still generate so much appreciation.

Twin Falls has always had this local hero (albeit not so well recognized as today) who just happened to be a surveyor, and that makes this community art story unique on several levels. A community embraces this hidden hero from its rich history, and the surveying profession has also found a new hero. But there are many other facets and potential long-term outcomes to this story. As Curtis Eaton said, “We envision this as a jumping off point for more community art and engagement. There was a starting point in 1904 and another in 2018.

Vision, Purpose, and Tomorrow

Learning about this project has changed me, as well. Like many of my fellow land surveyors, I tend to look at things a bit too clinically, concentrating on the land records and measurements, overlooking the positive impacts of our work for individuals and communities. Surveyors mostly work in obscurity, arriving in an area ahead of development, laying out the critical elements, and moving on before the folks who follow start toasting each other and basking in the success.

I learned a lot in researching this story, meeting the artist and the large team of dedicated community boosters for the project, speaking with Hayes’ grandchildren, attending the wonderful dedication event, and “retracing the footsteps” of this remarkable surveyor. I found that the real story is, as LaMure says, about heart and home.

Sometimes it takes someone from an unrelated field to truly capture the spirit hidden beneath the work. LaMure explained what it was that captivated him from his first look at that iconic photograph:

“I saw in that composition a coming together in purpose. The eye of a surveyor looking though a transit—the potentiality of phenomenal magic that can occur—that it could have influence, forever.”

See more photos in the carousel gallery at the end of the post

Dave LaMure Jr.

At age 12, LaMure was living in New Mexico, one of seven siblings. One day his uncle, an artist who was, as he put it, “a bit avant garde,” brought a large bag of clay to the house, dropped it on the kitchen table, and said, “Let’s see what we can do with this.”

LaMure took to it immediately and produced the sculpture of an owl. Later he visited a small studio at the back of a local museum and, when he saw someone there throwing clay on the wheel, was hooked.

Dave LaMure Jr. and his wife, Jamie, on the day of the dedication of his sculpture. Photo: Schrock.

He graduated from the University of Idaho with a major in business (and an almost-minor in art). He stayed, having been captivated with the region through guiding on the Salmon River. While he did some different lines of work along the way, his art was a constant, and he has been working in clay every year since he was 12.

His connections to the Twin Falls area have deepened with every passing year. He now lives on lovely property south of Twin Falls on the High Line Canal with his wife Jamie, his partner and inspiration (they have been together for more than 30 years).

LaMure finds yet another connection with Hayes: “He surveyed the High Line Canal. His footsteps crossed my property, and that connection raises the hairs on my neck.”

LaMure has worked in many mediums: sculpture, alteration of clay vessels (in particular with the Raku method of firing), figurative work, and figure drawing. He says he always found it easy because he was under the impression that everyone could do it. He later found out that not everyone could.

This artist had found his calling and has since been creating stunning, unique works that have garnered prizes and have been displayed at countless exhibitions, festivals, and museums across the U.S. Read more at davelamurejr.com.

The Trove

In search of Hayes’ related documents and photos, I found some at the local library, county museum, and newspaper, but hit the jackpot when I was introduced to Louis Zamora at the Twin Falls Canal Company (TFCC). Zamora grew up on a farm irrigated by the canals and is now an engineering technician and surveyor for the company.

Louis Zamora of the Twin Falls Canal Company is the curator of the historic survey records, maps, and instruments, including those of Hayes.

While Zamora says he does not often do the type of surveying Hayes did back during the original construction, the company is still a hub of activity. TFCC has continued to irrigate hundreds of thousands of acres, with some of the most affordable irrigation water in the country (for such a large system), with over a thousand miles of canals and laterals. Many are original, but substantial features needed to be added in the 12 decades since its original construction.

For irrigation systems to work well the land needs to drain well, in the best of circumstances through the ground and back into the Snake River. Farmers found that some of the land did not drain well, and water was percolating out of the ground. A network of drainage tunnels connected to outfalls high on the Snake River Gorge walls solved the issues. The tunnels and canals require upkeep—and a company trapper! One of the biggest hazards to the canals are critters burrowing in and under the embankments, from badgers to muskrats to crayfish (crawdads). A badger can burrow the width of a canal bank in a single day; the company trapper is always busy.

Zamora proudly showed me the trove of Hayes memorabilia in their maintenance facility. It’s not a museum per se, but I could imagine surveyors would greatly enjoy visiting if it were. The collection includes the original transit (a C.L. Berger and Sons transit built in Boston, #9347) reputedly used by Hayes in the establishment of the city. He also showed me many finely preserved spirit levels, stadia rods, tripods, chains, and tapes—all in remarkable condition (some surveyors know how to treat their equipment).

Hayes did foundational work for the canal company, so they have kept Hayes’ original field notes, beautifully drawn survey maps, and sketches. TFCC also has copies for sale (I could not find them through online bookstores) of the two books on the project previously mentioned. Contact TFCC at twinfallscanal.com.

Using the Future to Preserve the Past

A section of the 3D model of the commons and statue, scanned with an SX10 total station.

One month after the dedication, a local team of surveyors used high-tech surveying equipment of the present day to capture the site in a high-resolution 3D model for preservation purposes. The model was presented to the City of Twin Falls not only so they could feature it in any future 3D virtual or augmented reality tour or educational applications, but also as a high-definition as-built of the original should there ever be a need for repair or replacement—years, or even centuries from now. The forms from the casting of the statue were also saved for preservation purposes. The use of high-definition laser scanners is becoming an essential and common tool for historic site preservation.

Tom Ruby, PLS, and his crew from J.U.B. ENGINEERS Inc. (Jake Smith, CST III and Kirk Reichling, CST I) were joined by Eric Stricker, PLS, from surveying equipment and solutions dealer Frontier Precision, to map the Commons and scan the statue and other features.

To provide retraceable orientation for the map and 3D models, the team used a high-precision GNSS (GPS plus other navigation satellite systems) “rover,” a Trimble R10. Through network real-time kinematics (NRTK), the rover achieved centimeter positions for reference points on the site. A relatively new kind of surveying instrument, a robotic total station, with scanning and imaging capabilities, was used to capture features in both a high-precision scan and discrete mapping points.

The new city commons and statue of surveyor John E. Hayes were mapped with a scanning total station and a GNSS rover for preservation. In the foreground is a transit from the same era. Photo: Tom Ruby.

This scanning total station, their Trimble SX10 (read xyHt’s recent feature on these types of instruments: goo.gl/PTEcqT), seems like science fiction in contrast to the instruments of Hayes’ era. To highlight the contrast between the surveying instruments of today and those of Hayes era, Ruby brought an antique from that era, an 1880 Gurley surveyor’s transit, nearly identical to that featured in the sculpture. Ruby set it up next to the statue and modern surveying gear—some of surveying’s past meeting its future.

The high precision scan revealed something else: Tom Ruby said: “From the point cloud I was able to determine that the stone ended up within 0.11’ for distance and within 0.2’ for line” relative to the sculpted plumb bob and transit. Ruby added, “Pretty amazing when you consider that I laid that stuff out through phone conversations with Dave [LaMure] while he was at the foundry trying to tell me where the plumb bob would be in relation to the base. The contractor poured the pedestal which I had staked. Then they set the stone without asking me to check it, all while the statue was still in Joseph. Then Dave set the statue in place.”

Visiting the Magic Valley

There is much to see in and around Twin Falls and a sizable tourist trade. But now, knowing the story of Hayes, you might consider taking in a few more sites on that Twin Falls detour off Interstate 84 (surveying-related art or destinations can be few and far between) as a must-visit when in the northwest. Yes, we all know about the three surveyors on Mt. Rushmore, but this one might be a bit more relatable.

- The sculpture, “A Vision of Tomorrow” by Dave LaMure Jr, in the Twin Falls Commons, the corner of Main and Hansen Streets in downtown Twin Falls.

- Shoshone Falls, dubbed the “Niagara of the West,” a few miles east of Twin Falls.

- The Snake River Canyon, the site of daredevil Evel Knievel’s much ballyhooed failure to jump the canyon. Near Shoshone Falls Park.

- Hayes’ original point for the Twin Falls plat at the intersection of Main and Shoshone Streets. Do not go out in the intersection looking for the original stone.

- Milner Dam and the mouth of the main canal, about 20 miles east of Twin Fall—very pleasant countryside.

- Rock Creek Siphon, on the Low Line Canal south of Kimberly, Idaho.

- Minidoka National Historic Site, in Hunt, Idaho, 20 miles NE of Twin Falls. It’s the site of an internment camp, with an Honor Roll of nearly 1,000 U.S. soldiers, including many among the most decorated in WWII who fought for the U.S. while their families were interned.

- Twin Falls County Museum, four miles east of town on Route 30.

View from the I.B. Perrine Bridge, a stunning steel arch bridge that spans the Snake River Canyon as you enter town. Viewpoints on both sides and underneath afford excellent views of the canyon. In the distance is the spot where a daredevil attempted to jump the Snake River on a rocket-powered motorcycle.

Artist Dave LaMure JR. was invited to speak at Trimble Dimensions 2018, at the Sands Expo in Las Vegas. He spoke on the history and development of the iconic statue, but also had unique insights into the surveying profession, formed from his interaction with surveyors during this art project. Audio clip of his presentation below.

Audio clip of LaMure’s presentation at Dimensions 2018.

Additional Photos