As technology progresses and invariably becomes more accessible, people desire to re-evaluate previous works with the aim to increase accuracy and modernize maps. This is increasingly the case within maritime archaeology.

During the 1970s and 1980s a huge wave of underwater exploration was taking place across the United Kingdom, and many important archaeological sites were discovered. These sites include Henry the VIII’s Mary Rose, sunk in 1545 off the south coast of England, and the Dutch (VOC) East Indiaman Kennemerland, lost off Out Skerries, Shetland, in 1664. Both sites were meticulously dived, studied, planned, and excavated using the technology available at the time.

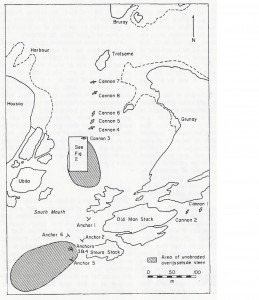

Taking the Kennemerland as an example, the team undertaking the excavation and recording of the site felt that the Ordnance Survey maps available at the time were not accurate enough for their requirements, so they set about redrawing the whole of the area where the wreck lies. Underwater archaeological features were then “shot in” using two land-based theodolites and divers holding buoys where they wanted a position. The plans of the site were then drawn up by hand and where required scanned for publication. The team estimated they achieved an accuracy of <1m.

1971 site plan of the Kennemerland by K. Muckelroy & R. Price, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology.

The Kennemerland is now designated as a Historic Marine Protected Area on account of the national importance of the wreck. Recently I was part of a team of archaeological divers sent to Out Skerries by Cotswold Archaeology on behalf of Historic Scotland. We were tasked with checking, updating, and geo-referencing the existing plans of the Kennemerland against what still survives on the seabed about 40 years later.

Initially we imported the current United Kindom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) charts into a GIS along with the scanned 1971 plan and attempted to match up features to geo-reference it. Whilst on one hand this was successful as the coastlines and stacks roughly aligned, we didn’t believe that it was accurate enough for us to locate the archaeological features with a view to positioning them using a DGPS system.

With the GIS and GPS running in real time on the dive vessel, we dropped divers on the newly positioned features and found that we were mostly within 10m, not accurate enough for the site plan but not bad considering we were working from a 40-year-old roughly geo-referenced site plan. On location of a feature, the orientation and description were checked to ensure we were on the correct feature, and then its position was recorded using the DGPS. For each feature several positions were taken and the results averaged to ensure a consistent and accurate result.

Following the positioning of some of the features to the north and the south of the site, the data was used as additional points in the geo-refrencing of the plan. We then found that the distances between features when measured on the seabed and from the 1971 plan in the GIS were becoming increasingly accurate at <2m. This enabled us to dive on a position with a fair level of confidence of finding the feature we were looking for.

Not all the features on the 1971 plan were located during the course of the survey. In some instances this was due to limited time, but some features we were unable to locate on the seabed at all. The area in which the Kennemerland wrecked becomes heavily overgrown with kelp during the summer months, which can make the location of features difficult, and some of the features have been removed from the seabed and can be found in locations over the island. Therefore, a reconciliation between our survey and the archaeological record would be required in order to be more certain that we hadn’t missed something.

The team agreed that the original site plans were likely to be good as they were created by pioneers in their field, but there was also the expectation early on that this was an exercise in reposition-fixing features, undertaking long searches underwater, and removing any inaccuracies. What it became, however, was an exercise in verifying realtionships between features measured 40 years ago with relatively low-tech equipment and finding that the level of accuracy was not far off what is achievable today in this sort of environment.

The results, positions, and modern charts will be used to create a digital geo-referenced site plan that will aid Historic Scotland in the continued protection, management, and promotion of one of Scotland’s most important marine heritage sites.

Click here for more information on the wreck of the Kennemerland.