Seniority of Title and Forward Search

I am often a part of litigation involving surveying services and research mistakes. (I must admit that, in excess of forty years of practice, I have made my share of mistakes performing record research.) I’ve observed five common research mistakes often made by surveyors. This article explains the common mistakes made by surveyors when determining senior title and when researching records.

Seniority of Title

Many surveyors are under the misunderstanding that once a person conveys property, that person cannot subsequently convey good title in the same property to another person. This is never true. In fact, there is not a single state recording act that would place senior title with the first grantee unless the grantee took immediate steps to record the deed or take possession of the property.

The recording acts in all states fall into one of three general categories of statute: race, notice, and race-notice. The general definition of each category is the following:

- Race: The first person to record his or her deed has senior title regardless of the sequence the conveyances were made or the knowledge a grantee had of an earlier conveyance.

- Notice: The last conveyance made where the grantee did not have notice of an earlier conveyance has senior title.

- Race-Notice: The first person to record his or her deed—who was conveyed the property without notice of an earlier conveyance—has senior title.

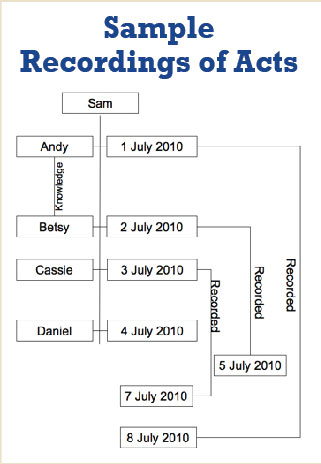

Consider the following example, in Figure 1. Sam conveys a lot to Andy on 1 July 2010. A short time later, Andy tells Betsy that he purchased the lot from Sam. Betsy goes to Sam and offers to buy the same lot that Sam sold to Andy.

Even after Sam explains to Betsy that he has already conveyed the lot to Andy, Betsy insists on paying money to Sam in order to obtain a deed to the lot. Sam, with marginal ethics, goes for the money and conveys the same lot to Betsy on 2 July 2010 that was previously sold to Andy.

Sam now realizes he can make a considerable profit if he keeps conveying the same lot to other individuals without knowledge of an earlier conveyance of the lot. Consequently, Sam conveys the same lot to Cassie on 3 July 2010. On 4 July, Sam conveys the same lot to Daniel.

On 5 July, Betsy records her deed (thereby providing “the world” constructive notice of a conveyance of the lot from Sam). On 7 July, Cassie records her deed. On 8 July, Andy records his deed. Daniel never records his deed.

Even though Andy was the first conveyance from Sam, he does not have senior title under any of the recording acts.

Under the “race” category of recording act, Betsy has senior title. Betsy was the first to record a deed to the lot.

Under the “notice” category of recording act, Daniel has senior title. Daniel was the last person to be conveyed the lot without notice of an earlier conveyance. In fact, Daniel will have senior title under a notice category of recording act even though Daniel never records his deed.

Under a “race-notice” category of recording act, Cassie has senior title. Cassie was the first person to record a deed from Sam that was delivered to her without notice of an earlier conveyance.

As can be seen from this example, without knowledge of the category of a state’s recording statute, surveyors will often terminate their record research prematurely or will mistakenly determine that senior title resides with the wrong person in a situation such as an overlap.

A surveyor should take the time and determine what category of recording statute is effective in his or her state. At least two states have more than one category of recording act in effect.

Forward Search

Many surveyors perform a record research back in time but fail to perform a search forward in time. As a consequence, the surveyor will often miss recorded out-conveyances from a parcel. The surveyor will also fail to find other recorded documents (e.g., boundary agreement) related to the boundary of the parcel being researched.

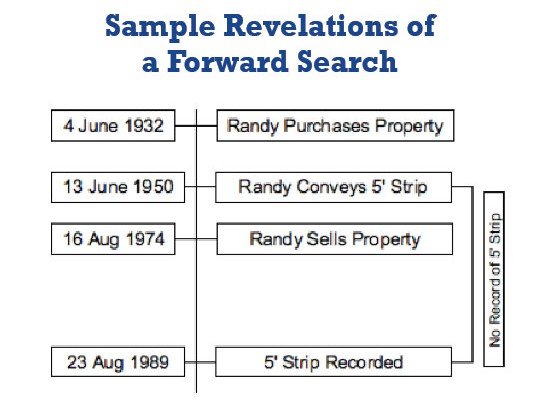

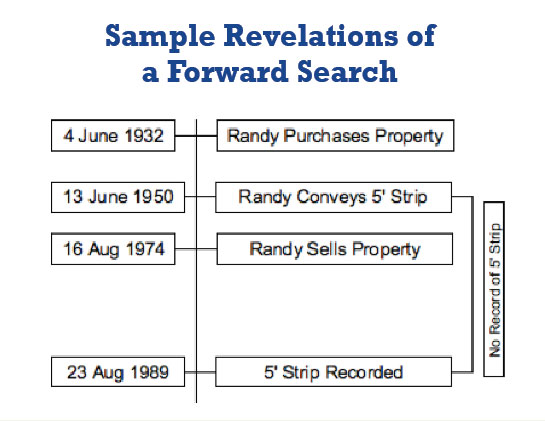

Assume a research of the records has disclosed that Randy owned a residential lot from 4 June 1932 to 16 August 1974 (Figure 2). On 13 June 1950, Randy conveyed a five-foot strip of his residential property to his neighbor, by a properly executed deed. The neighbor built a fence along the new boundary on 2 May 1954 (thereby providing notice).

On 16 August 1974, Randy conveyed the residential lot to Bill. The deed from Randy to Bill used the original description and did not mention the five-foot strip conveyed to the neighbor 24 years previously.

On 23 August 1989 the executor of the neighbor’s estate discovered that the deed for the five-foot strip from Randy to the decedent had never been recorded. The executror recorded the deed for the five-foot strip on 23 August 1989. Although the deed was executed in 1950, the deed was indexed in the indices covering the 1989 period when the deed was finally recorded.

If a surveyor fails to perform a forward search, the surveyor will not discover the recorded deed conveying the five-foot strip of land to the neighbor. The surveyor, with Bill as a client, would believe the fence was encroaching on Bill’s property

This example illustrates that a complete record search entails using the name of a previous owner and searching every grantor index from the time the property was conveyed to a predecessor in title up to the present time. This procedure is known as a forward search. Unless a forward search is performed, the surveyor will not discover some conveyances that were made, were properly indexed, and are effective against the title to real estate.

Bringing to light a surveyor’s failure to perform a forward search will not necessarily convince surveyors to undertake the tedious and time-consuming research necessary to overcome this limitation. Yet, the failure to perform this task could expose the surveyor to liability.

At the very least, the surveyor should inform the client that these deficiencies in the research exist at the completion of services. Should the client want to compensate the surveyor for the time to perform a thorough search, these limitations can be overcome. n

Look in future issues for articles on the remaining three research mistakes surveyors make.