Katmai National Park broke new ground in laser scanning this October when a survey-grade scanner was used for their annual “Fat Bear Week.”

Traditionally, the fatness of many a Katmai Park brown bear has been voted on by awe-struck online onlookers—the park has several webcams—and has been a matter of personal opinion gauged by eye. Votes are cast on Facebook, via “Like.” None of that changed for 2019—it was simply brought into semi-precise, scientific sight with the application of a Trimble TX8 scanner.

Joel Cusick is a GIS specialist with the National Park Service. Having discovered Fat Bear Week during a professional visit to Katmai, he realized he could gather bear fatness data with volumetric equipment he’s accustomed to.

Cusick says, “It’s [otherwise considered] impossible to get fall bear weights due to size. They simply can’t lift a fall bear using tripod/pulley in the field, so this is a possible way to derive what is otherwise impossible to measure on such large creatures.“

How do you plan to scan a bear?

Cusick says, “I had made an initial investigation the year before by scanning the bears […] with an SX10 at an approximate distance of 380 feet. Those provided some promising results.

“I created a small polygon using the high zoom camera to delineate a small area surrounding the bear, and in concert with the integrated camera I was able to view directly enough laser returns from the surface of the large bears.

“A year passed, and […] I brewed up this as another job to conduct during the next fall season. During this time, the Park Service GIS team became more proficient at scanning while taking classes from the Trimble dealer in Anchorage, Frontier Precision.”

Where do you scan a bear?

In 2019, Dan Butvidas of Trimble accompanied Cusick, along with Cusick’s wife, Jackie Carney, and Mike Anderson (a biologist, formerly with the Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game) back to Brooks Camp, where they employed a fleet of technology to accomplish the several requested surveys.

“The bears at Brooks are quite like clockwork when they show up at the falls and other locations in the area,” says Cusick. “They are monitored by Katmai National Park rangers, and during the week we were advised that some of the larger bears would likely be at the falls in the early evening hours.

“This is a prime viewing area and, as it turned out, a near-perfect place to scan bears from up close. A raised platform allows visitors to watch the bears.

“We set up a Trimble TX8 scanner at a location along the elevated boardwalk to minimize our impact on the human visitors.

“We assembled at the falls platform accompanied by Tammy Carmack, a bear monitor for the National Park. Tammy provided a key element in this survey—positive identification of the bear to ensure accuracy.

“After we established two survey points on the platform/boardwalk (using RTK with the Trimble R10) and used the Trimble Realworks Station Setup workflow, we tied scans from the platform to the Katami control network.” Butvidas added, “Scanner placement was on a wide section of the walking platform, behind the view area. After initial testing, this was an ideal location. [The] bear-only area was unobstructed for scanning bears and not in the viewing platform area to disturb the visitors from their bear watching experience.”

Why do you scan a bear?

Butvidas and Cusick used Trimble RealWorks to calculate surface volume on one half of each bear (the side facing the scanner) using a three-point plane method. The derived volume was then simply doubled to make an estimate of full body volume for the bears.

For example, Bear 747, a large male bear, was estimated to have a full body volume of 23.4 cubic feet from the scans. Using a rough approximation of a fall bear’s weight, determined by 65% water and 35% fat, the densities of water and fat were multiplied by the volume to determine an estimate of weight at 1408 lbs. A bear called Walker was a good test for precision because he was scanned twice, and estimates of his volume between the surveyor and GIS specialist came within 5% of each other.

Would you scan a bear again?

Subsequent to the success of scanning at Fat Bear Week, Cusick says that volumetric scanning for “polar bears in Kaktovik [has] been suggested, since those are even bigger and are, as you might imagine, one of those species on the forefront of arctic warming.”

CNN’s article on this subject notes that polar bears and brown bears will become dining rivals with the decline of the latter’s sea ice hunting grounds. Ironically it’s that dining that allowed Joel and his team to grab their moments. The platforms they scanned on were placed where the salmon are abundant: a bear who is fishing is a bear who is standing mostly still.

Despite that, Dan notes, “Water is a limitation to scanning; what is below the water, the scanner cannot provide the data [for].”

Joel says, “Timing [was] key when we were targeting the likely ‘winners’ of the fat bear contest.”

A shot from the primary camera of the scanner shows the point returns (380 feet) of Otis, a popular bear at the falls, sitting in the “office.”

What if you can’t scan a bear?

The team was disappointed they were not able to scan the bear voted by the public this year as the fattest bear. Holly, aka Bear 435, took her crown after beating out others (such as Walker, Divot, Lefty, Otis, and Chunk). Holly was estimated at a little under 800 lbs, and other bears featured within this year’s tournament were pinned at weights of up to 1408 lbs, making “give or take fifty” a reasonable enough guess. Would you argue it with a brown bear?

The sexual dimorphism of brown bears means that on average, female bears weigh around a third less than male ones. That explains why winner Holly’s estimates are all lower than her brother bears’. Bear fatness isn’t just about weight, it’s about potential for survival: during winter hibernation the resources conserved in that fat are vital. Holly is a smaller bear than, for example, Walker, and she has a different metabolism. Her fatness is particular to herself and her needs.

Brown bears are not especially endangered today—they have an estimated worldwide population of 200,000—but climate shift will be changing their environment as much as it changes ours, and it’s good to know Holly is predisposed to survive.

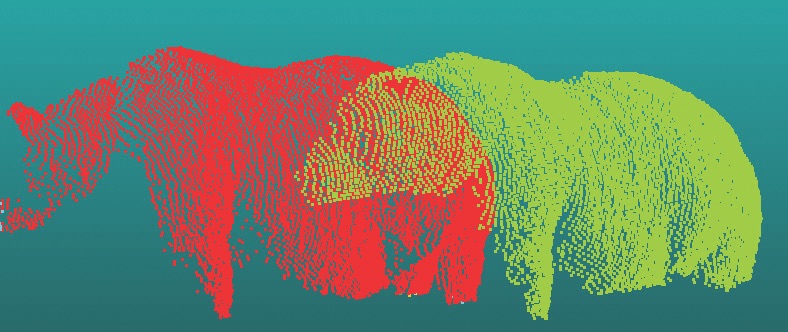

Banner image: Two scans of two bears that were in the same area of Brooks Camp, Alaska, at different times.