Breakthrough User Successes for the Fledgling Technology

By Geoff Jacobs

In my previous article in this series (May 2021), I detailed the big, positive impact that Leica Geosystems acquisition of 3D scanning start-up, Cyra Technologies, in 2001 had on the emerging 3D laser scanning market. Leica’s entry not only legitimized the new technology for many prospective users, but it also aided and encouraged other early 3D scanning product vendors.

In this article, I’ll describe the early user community as Leica was in the process of entering the 3D scanning products business. Although most users at the time were struggling, there were some well-publicized breakthrough user successes that reinforced their belief in the technology’s upside.

Early User Struggles

Two breakthrough plant projects for 3D scanning gained widespread exposure; a Detroit Edison power plant retrofit (top and lower left) and a Chevron off-shore oil platform retrofit (top right). The Detroit Edison/WGI project won the prestigious NOVA award for innovation from the Construction Industry Forum.

Image credits: Greg Lawes; Bentley; and Chevron.

Early users and dealers largely struggled to make a return on their significant investment in scanners, software, training, etc. There were several factors. First, field and office efficiency of first-generation solutions were simply not cost-effective versus traditional methods for everyday applications like topographic and site surveys, building/existing conditions surveys, construction QA, forensic/crime scene surveys, and others.

Office workflow options were limited, and early workflows were time-consuming. It was not uncommon to see a 10:1 ratio of “office time to field time” — and remember, this was when doing 20 scans per day was considered maximum field productivity.

Scanning was only being successfully applied to the most difficult mapping and as-built projects — often where traditional methods were not feasible. That there were so few of those special applications was a real business problem for many early scanner owners.

Marketing 3D laser scanning services to prospective clients was also difficult. Many clients didn’t want or need 3D. Scanner prices were also quite high (typically more than $100k) and scanners were still relatively heavy and awkward to deploy compared to total stations.

Computers and data storage had to be upgraded. In the office, users needed CAD techs skilled in 3D, a rare breed back then. Point cloud software was not easy to learn and unless a user used it frequently, users would quickly become inefficient with it. Times were tough.

Although most users struggled, many got into it knowing the technology was in its infancy, but, as early adapters they could see the technology’s potential and wanted to gain an early competitive advantage with it. Every successful project reinforced their belief.

Major User Success Breakthroughs

For any new technology, well-publicized reports of early “breakthrough” user success stories — ones that scream, “Wow, this stuff is great!” — are critical for stimulating additional interest in the technology. For 3D scanning, those early, widely publicized breakthroughs happened in three application areas: industrial

plant retrofits, a civil infrastructure survey, and scanning famous statues.

Industrial Plant Breakthroughs

Two were wildly successful and widely publicized.

Detroit Edison Power Plant Retrofit

Cyra’s beta user partner Raytheon E&C/WGI applied the first-generation Cyrax 2400 and CGP point cloud software on a $250 million retrofit of Detroit Edison’s Monroe fossil fuel power plant. A large, environmental compliance SCR system had to be located where original plant designers had not intended anything else to be located. Steel supports, ductwork, piping, etc. had to be installed in, around, and through existing equipment and structures. An accurate 3D as-built model of major portions of the 10-story high plant was needed for retrofit design and construction planning.

Greg Lawes and Derrel Shaffer led the Raytheon E&C/WGI as-built team. The project’s scanning metrics (e.g. 10 minutes per 40º x 40º scan; 51 scans total over five days) are dwarfed by today’s 3D scanning system capabilities. The office workflow — converting scans to geometric primitives in point cloud software and exporting those via DGN to MicroStation — was tedious, but the bottom-line benefits were fantastic.

Veteran WGI project manager Bruce Klein estimated that using 3D scanning had saved the project $10 million by avoiding typical retrofit construction clashes and fit-up problems. Yes, $10 million. Klein gave an on-camera interview to Cyra’s Laslo Vespremi stating that. Cyra then used that video countless times to educate the plant design and construction industry about the practical benefits of 3D scanning.

The use of 3D scanning on that project earned Detroit Edison, WGI, and Cyra the Construction Industry Forum’s prestigious NOVA Award in 2001 for construction innovation. In fact, in those early years, many other early users of 3D scanning earned similar “innovation awards” from local organizations such as state surveying organizations. The project was a four-page feature article in the January 2000 issue of Bentley’s MicroStation Manager magazine and was also covered by ENR magazine.

Chevron Off-shore Oil Platform

Another breakthrough plant retrofit project using Cyra’s first generation scanner and software also wound up with its project manager, Floyd Sanders, talking on camera about it. The $2 million project involved replacing a large vessel on a tightly packed off-shore oil and gas platform with an even larger vessel, increasing capacity by 70 percent. Chevron funded the $50,000 scanning/as-built modeling service out of a $200,000 (10 percent) contingency in the project budget. A first-generation scanner and point cloud software were used to create an as-built model, which was used for retrofit design and construction planning.

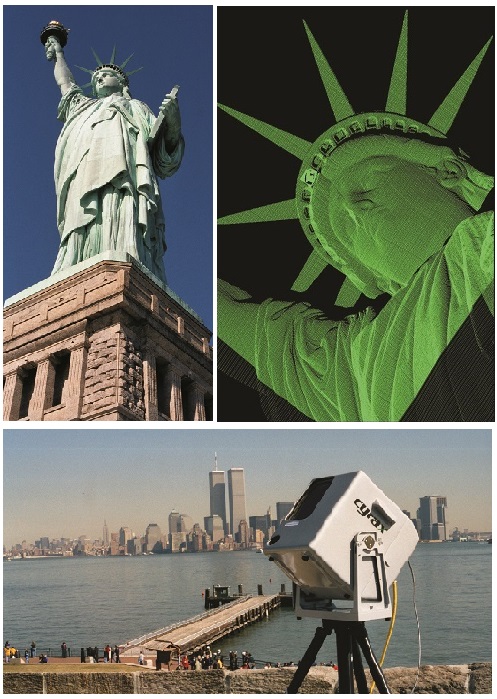

3D scanning of the Statue of Liberty was done just three months before 9/11. The World Trade Center towers are in the background of the Cyrax 2500 scanner as it scans Lady Liberty. This scanning project gained widespread media attention for the technology’s potential to preserve heritage assets. Image credits: Texas Tech University and Geoff Jacobs

Although the project was small, there were several very notable aspects. First, using scanning achieved well-documented cost savings versus manual as-builts: fewer helicopter trips to the platform; more than 50 fewer on-site welds; and, avoidance of any construction clashes and fit-up problems, which would have otherwise been anticipated.

However, the biggest documented benefit of scanning was something else. Sanders cited a reduction in the shutdown period from the planned 72 hours to actual 40 hours. That translated to more than $1 million in additional revenue from the platform. The breakthrough lesson learned from this well-publicized project was that reducing the risk of extended downtime (common for retrofit projects) was Chevron’s major driver for using 3D scanning instead of risky manual as-builts that were often inaccurate.

Chevron presented this project at Houston’s prestigious Daratech Plant Conference to an audience of hundreds of plant industry executives. Moreover, the video of Chevron’s Sanders talking about the project was shown countless times in the following years. That documented benefit — reducing retrofit downtime risk for a production asset — would play out time after time over the years ahead.

The final big breakthrough win from this project was that it validated the benefit of 3D scanning off-shore platforms. Before long, using scanning to create accurate as-builts of offshore platforms became one of the very first “sweet spots” for the technology. Some of the technology’s largest early service providers focused on offshore platforms. A similar early sweet spot for scanning was its beneficial use in nuclear power plants.

Highways to Success

A breakthrough project in 2000 used a first-generation Cyrax 2400 scanner and CGP software to open users’ eyes to the new ability to survey busy roads without occupying the roadway or shutting down traffic lanes. The well-publicized project also demonstrated the practical benefit of elevating a scanner to increase its useful range on ground surfaces.

The project was a design topographic survey for a planned widening and bridge replacement of a four-mile stretch of Highway 880, a major Silicon Valley commute corridor. Civil/survey firm Mark Thomas of San Jose, California, worked with a vendor to develop a boom “cherry picker” truck that held the scanner 35 feet high. Project manager Tom Milo claimed that using 3D scanning on that project (at which they surveyed about one-half mile per day) cost about the same as traditional survey, but they did not have to close any lanes, did not have to work at night or on weekends, and did not have to stand in the roadway to gather data. They also collected more detailed data that Milo concluded was as accurate as a traditional survey.

This project wound up as the July 2000 cover story for a leading survey industry trade magazine. Milo also agreed to be videotaped to discuss the project. Just like the two other videos, this highway survey video became a popular marketing tool that was used to educate many prospective civil/survey firms, especially departments of transportation. It didn’t take long for this roadway application to become another early sweet spot for the technology.

Famous Statues: David and Lady Liberty

Nothing helps exposure for new technology like getting it favorably into the public eye. That happened twice in a huge way in the 2000-2001 timeframe.

The Digital Michelangelo Project was another early breakthrough project that widely publicized the ability of 3D scanning to accurately capture heritage assets.

Images courtesy: Stanford University and Riegl

The “Digital Michelangelo” Project

Stanford University, via Marc Levoy’s computer science team — used three different types of digitizing tools, including a Cyrax 2400 laser scanner, in 1998-1999 to capture detailed surface geometry of some of Michelangelo’s

most famous works. Their research goal was to make precise computer surface models of those works. In 2000, the first public results of their efforts were presented at SIGGRAPH 2000.

The news quickly made worldwide headlines in more than 60 newspapers, magazines, TV programs, Internet news sites, and other media. What garnered the greatest attention were scans and surface models of the Statue of David, as Stanford reported that the actual height of the statue was quite different than otherwise popularly referenced.

The main digitizing instrument was a custom, gantry-mounted, laser triangulation stripe rangefinder, which was used to scan the statue at very close range with dense detail (0.29mm spacing). It was provided by Cyberware (Monterey, California). A Cyrax 2400 3D scanner was used to scan interiors of buildings and halls in which the works, such as David, were located. Another tool used on the project — a digitizing arm — was provided by Faro. This was several years before Faro got into the 3D scanning products business via their acquisition of iQvolution (Germany) in 2005, but one wonders if this well-publicized project didn’t open Faro’s eyes to the potential of large-scale 3D scanning technology.

Statue of Liberty

This global icon was 3D scanned in March 2001 as a feasibility test for digitally recording and preserving large, historic assets. The test was sponsored by Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and the National Park Service (NPS), which is responsible for maintaining Liberty Island. Teams from Texas Tech University (which had just purchased a Cyrax 2500 laser scanner), Cyra, and Leica collaborated on the project. The feasibility test proved successful and final, full 3D scanning was completed in June 2001 — just three months before 9/11.

After 9/11, the story of 3D scanning of Lady Liberty captured global interest and newspaper headlines. American intelligence had received information that Al Qaeda might strike U.S. landmarks like Liberty. The story line was that a 3D laser scan-based computer model could be used for precise reconstruction in the event of a catastrophe. In February 2002, Professional Surveyor magazine (now xyHt magazine) ran a famous, front cover feature article on the project.

3D scanning of statues and historical buildings was already well underway as an early application of 3D scanning, especially with universities, but widespread publicity about the Digital Michelangelo project and the Statue of Liberty project propelled that application to lofty, new heights.

In my next article, I’ll describe the early competitive landscape of 3D laser scanner vendors and point cloud software vendors, a very different and much-less-crowded landscape than today’s.