The largest single-instrument geophysical survey ever in America hopes to uncover some of the mysteries of the Cahokia Mounds

Long, long before any of our great Mississippi River cities, and long before Europeans landed on New World shores and pushed westward, Native Americans were thriving in an urban center so big and so complex it rivaled some of the great Mesoamerican civilizations of Central and South America.

A representation of what Monks Mound (in the distance) and Cahokia might have looked like.

Home to perhaps as many as 20,000 in the “city” and “suburban” farming areas, Cahokia was a bustling center of trade for communities across much of what we now identify as America. Just across the Mississippi River from modern-day St. Louis, archaeologists believe humans were extensively occupying the American Bottom landscape by the 9th and 10th centuries CE, before Cahokia rose to be the most important Mississippian city by the 11th and 12th centuries.

Mesoamerican civilizations like the Maya, Inca, and Aztec have been so thoroughly studied through mysterious ruins like Chichen Itza, Teotihuacan, Tikal, and Machu Picchu that a picture of what life was like among those cultures has emerged. What life was like in Cahokia, how it rose to prominence, and why it was abandoned remains a vague image. Civilizations of Central and South America built stone structures that survived for centuries after abandonment, but much of Cahokia was built of earth and wood, much if it long-since decayed. The picture of Cahokia that has been emerging centers around enormous earthen works, many of which have survived.

One such work, known as Monks Mound, is the largest pre-Columbian earthwork in the Americas. Construction of this monument is thought to have started in the early history of the site. The mound covers 14 acres, rising 100 feet high and was topped by a 5,000-square-foot building, likely a temple or residence of the paramount chief. The amount of earth moved–by handmade baskets–to create Monks Mound would fill the Great Pyramid of Giza, meaning the mound and structure dominated the area and likely could be seen from almost everywhere in Cahokia.

Casey Barrier conducting a pilot mapping project at Cahokia in 2016 with Monks Mound in background.

Why Native Americans settled in the area of what is now Illinois near the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers appears to be very well understood. During the Medieval Warming Period, this very fertile stretch of land, now aptly referred to as the American Bottom, provided a place to grow maize, beans, and squash as cultures of the time transitioned from nomad hunters and gatherers to agricultural communities that settled in one place. Answers to other questions—such as how the civilization grew and why it disbanded, fell apart, or was forced apart—are not as easily answered.

Next month, a group of archaeologists is hoping to begin to change our understanding of Cahokia by conducting

Edward Henry pushing a Carlson RTK rover at the Cahokia Mounds site.

the largest single-instrument geophysical survey ever in the Americas. Led by Edward Henry, assistant professor of anthropology and geography at Colorado State University, and using Carlson RTK BRx6+ and BRx7 GPS systems, the survey will provide the first nearly total geophysical survey of Cahokia’s subsurface landscape. Combined with GIS and spatial analyses, the team hopes to “see” Cahokia from a bird’s-eye view, providing an unparalleled opportunity to compare the city’s density, organization, and growth with others around the world.

Henry and his colleagues, Casey Barrier, associate professor of anthropology at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia; Robin Beck, professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan; and archaeologist Tim Horsley, owner of Horsley Archaeological Prospection, LLC , received a five-year $312,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to conduct the survey.

Hopefully the survey will provide unique insights into the ways that Indigenous people in the American Bottom coalesced to form the largest precontact community in North America.

“The resulting map will be a powerful tool in its own right,” says Horsley. “That will allow us to look at the use of space and settlement organization across the entire landscape.”

Artist’s conception of the Mississippian culture Cahokia Mounds Site in Illinois shows Monks Mound at the center of the site with the Grand Plaza to its south. Three other plazas surround Monks Mound to the west, north, and east. To the west of the western plaza is the Woodhenge circle of cedar posts, thought to be similar to Stonehenge in England.

The Carlson equipment will ensure every five-centimeter pixel of data representing subsurface magnetic change is spatially accurate to a sub-centimeter resolution. “It’s phenomenal to have that level of precision,” Henry says.

The Carlson’s GNSS receivers will track the location of the survey’s scanning system as it moves across the site. Carlson’s field software SurvPC will feed spatial location, matched with the geophysical readings, into their data collection systems. The Carlson rovers will be mounted to multi-sensor gradiometer carts and towed by all-terrain vehicles to cover large areas quickly and accurately. The GPS sensors eliminate the need for creating and moving physical grid lines.

“Every second the machine is going to know where it is…so we can cover a lot of ground really quickly,” Barrier says.

The team’s preliminary subsurface magnetic surveys at Cahokia using multi-sensor gradiometer systems reveal that there is much data essential to understanding the emergence of Native American urbanization to be collected. The next step is to take up the challenge of investigating an urban-scaled phenomenon. So, the team devised a methodology and approach to produce a massive, large-scale spatial dataset to create an overview of Cahokia.

“I think this survey will reveal how the earliest communities that lived in close association to one another organized themselves into neighborhoods, and how those neighborhoods were distributed and served as a foundation for what we see as the first durable expression of urbanism among American Indians prior to European arrival,” says Henry.

The team’s survey will help to better understand the global move toward urban life and also understand aspects that made Cahokia unique.

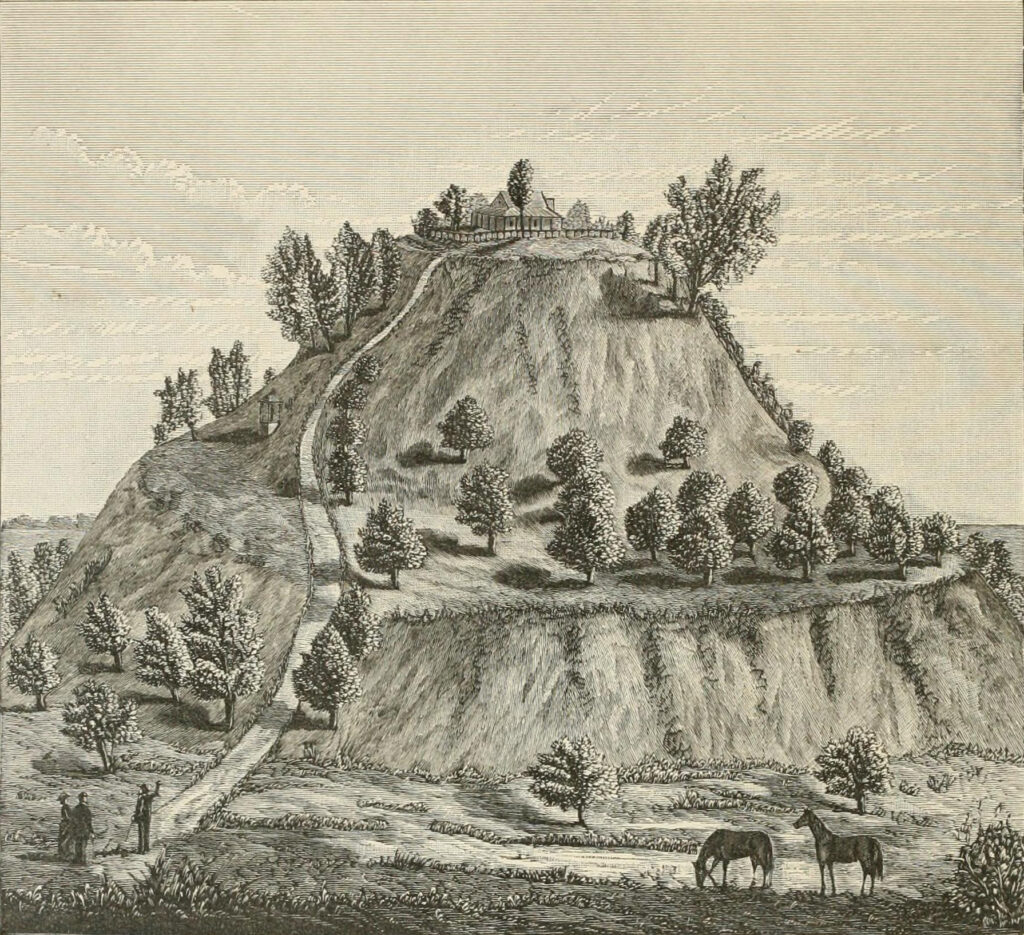

An 1882 illustration of Monks Mound showing it with fanciful proportions.

“One of the exciting things that has grown from the study of early urban places worldwide is the recognition that there was more than one way to organize a city, and the spatial layouts of human settlements tell us something about its history and the social aspects of the societies that built them,” Barrier says. “The archaeological and historical information about early cities around the globe is growing rapidly, collected at sites in the Middle East, the Mediterranean region, across regions of Asia, Africa, and Meso- and South America. This project is one way to study Cahokia as an early urban place alongside other important sites on other continents.”

The team is hoping that using Carlson equipment to help scan beneath the surface will move the archaeological knowledge in the direction of a clearer picture pertaining to the development of Cahokia. What is certainly known is that Cahokia was once home to as many as 10,000 to 20,000 people and likely was the largest urban center on the continent north of the great Mesoamerican cities of Mexico and Central America.

“You can think of it as an X-ray image of what’s preserved under the surface,” says Barrier. “So, in terms of preservation of the site, we won’t put a shovel or a trowel into the ground. Yet, the research will provide important information about how humans organized themselves in early cities. And Cahokia is one of a handful of places across the globe where humans initiated urban life without direct contact with other urban societies.”

The Carlson equipment and software will help identify buried house locations, storage or refuse bins, and other modifications to the landscape like the production of plazas. “Long after the wooden superstructure and roof has decayed or been taken down, magnetometry can detect the footprints of buildings and houses,” Barrier says.

The team also hopes the survey will offer a new kind of experience for people who visit the site or explore its history online. Cahokia meant different things to the many people who lived and worshiped there, and this project should bring more of that to life in the guided tours and interpretive center’s theater and exhibit gallery.

“By partnering with descendent communities who view Cahokia as an ancestral place, we hope to help create a project that’s truly collaborative,” says Beck. “Indigenous stakeholders can help us to better understand the patterns we see in the data, creating the potential for narratives that draw on different ways of seeing the past.”

The importance of Cahokia cannot be underestimated. “During its peak in the 10th to 12th centuries CE, native inhabitants constructed more than 120 earthen mounds, plazas, and neighborhoods, spread out over approximately 15 square kilometers, making it orders of magnitude larger than any other archaeological site north of the Rio Grande,” Barrier says.

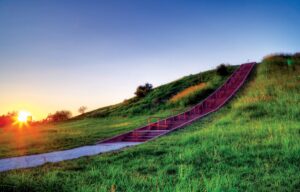

A modern concrete stairway has replaced the wooden stairs leading up the first level of Monks Mound.

Cahokia is one of the most studied archaeological sites in North America, but even after decades of work, some of the most fundamental facts about its growth and organization are not wholly understood.

Prior excavations have covered only about one to two percent of the site at most. Surface artifact collections, and various forms of mapping, most recently with lidar and small geophysical surveys, have been crucial to gaining an understanding of the site. How it will all fit together with the team’s survey has yet to be determined, but Henry says, “We will certainly be integrating maps of previous excavations across the site, for instance, around the interpretive center and museum where several houses were uncovered.”

“Much of this work has challenged earlier interpretations of the site and scholars are now productively viewing Cahokia as an urban development, meaning that Cahokia was the first city ever built in North America,” Barrier says.

For Carlson, the Cahokia survey is another example of how their equipment is helping to uncover historical aspects of archaeological sites around the world. Without such technology, much information about earlier civilizations would remain a mystery.

Dave Atkinson of Westlat Design in Parker, Colorado, first suggested the Carlson geospatial systems to Henry and has facilitated purchase of the Carlson equipment, and donated several additional equipment items, to help the research team at Cahokia. Atkinson also introduced Henry and the Cahokia project to Jim Reinbold, Carlson Software’s regional sales director, who has helped the team secure additional equipment needed to complete the project.

Reinbold notes, “Helping tell this story of American history is really an honor, and pretty exciting, too. Carlson’s software and hardware solutions have been used on thousands of projects around the world, but this case is really cool. It’s in another category, and we’re really honored to be involved.”