A small university on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is educating the next generation of surveyors and geospatial engineers

Douglass Houghton was Michigan’s first state geologist, but he was also a mineralogist, chemist, doctor, politician, and surveyor. His love was the natural world, and in the mid-19th century he led a linear and geological survey of the state’s Upper Peninsula.

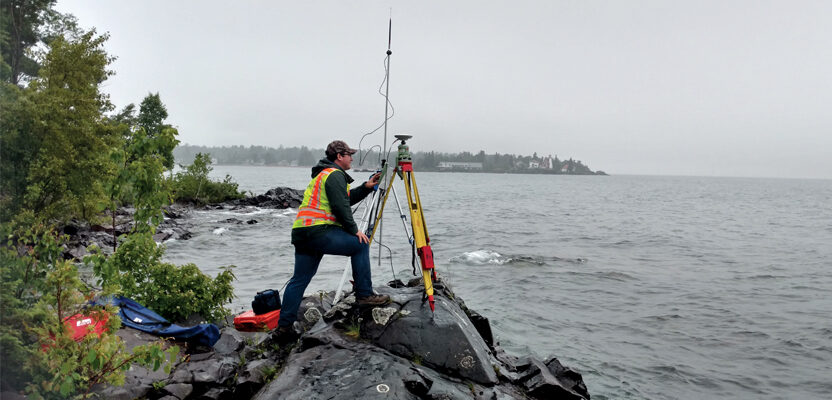

Students at Michigan Tech survey Lake Superior, continuing the work started almost 200 years ago by Douglass Houghton.

Houghton’s life was tragically cut short during an 1845 survey of Lake Michigan when the boat he was working in capsized in a storm, but his impact on the UP lives on in the city of Houghton, where Michigan Technological University is educating the next generation of surveyors and geospatial professionals.

The student chapter of the National Society of Professional Surveyors is named in Houghton’s honor, and like Houghton, the geospatial engineering students at Michigan Tech value the natural beauty of the Keweenaw Peninsula as they apply the skills they learn in class to further map and measure the area that Houghton explored.

“The beautiful Keweenaw Peninsula of Upper Michigan is our home and laboratory,” says Jeffery Hollingsworth, a professor of practice in the geospatial engineering program. Hollingworth is a professional surveyor and GIS-certified professional with 40 years of industry experience, including owning a surveying and mapping firm.

The Redridge Steel Dam students at Michigan Tech surveyed environment damage and structure deterioration and with 3S scanning created a three-dimensional model of the 120-year-old structure.

He recently led a class trip to the Redridge Steel Dam—a flat-slab buttress dam constructed of steel in 1901 in Houghton County, Michigan. His geospatial engineering students explored environment damage and structure deterioration with 3D scanning of the structure. They also conducted an unmanned aerial survey from above.

“The point cloud data our students produced will be used to construct a three-dimensional model for submission to the National Historic Places,” says Hollingsworth. Then he plans to work with a class of civil engineering students to consider methods of restoration of the concrete and structural integrity of the 120-year-old design.

“The beauty, topography, and opportunity in the Keweenaw Peninsula influences the education we provide, but the world is the geospatial program’s classroom,” says Audra Morse, chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Michigan Tech’s geospatial program enables students to learn both in nearby Houghton and from faraway places as well. This fall semester 2021, all geospatial engineering courses will be offered both on campus and online, a first for Michigan Tech.

“We believe serving students via online education will address the growing need for more land surveyors and geospatial professionals,” says Morse.

With an ABET accredited engineering degree from Michigan Tech, graduates are able to pursue professional licensure in all states, including Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Minnesota, says Morse. “For states requiring only a certificate, our geospatial engineering degree easily meets licensure requirements.”

The same great faculty teach both on campus and online. Small class sizes allow the faculty to know the students and engage them on the path to student success.

“Every one of our students has either secured a job, or has been working, before they even graduated—and were given multiple offers along the way,” notes Joe Foster, a professional surveyor and professor of practice at Michigan Tech.

Foster previously worked as a principal for land surveying companies in Minnesota and Michigan, directing and overseeing a wide range of projects. He is a member of the Michigan Society of Professional Surveyors (MSPS).

At Michigan Tech, he’s advisor to the Douglass Houghton Student Chapter of the National Society of Professional Surveyors (DHSC). Last year the group continued its tradition with an annual General Land Office (GLO) Workshop. Sponsored by DHSC and conducted by Pat Leemon, PS, retired U.S. Forest Surveyor from the Ottawa National Forest, the workshop involveed a search/perpetuation of an original GLO corner.

“That’s a once in a lifetime experience for a surveyor,” says Foster.

At Michigan Tech students get the right blend of instruction to prepare them for professional licensure, says Foster. “That includes plenty of the hands-on experiences needed to accomplish the work. Our graduates are ready to do the job from day one. We also have a very good rapport with our professional and industry partners. They come looking for our graduates.”

Faculty credentials are an important differentiator at Michigan Tech. “Between myself, Joe, and Eugene Levin, we have nearly 100 years of geospatial experience,” says Hollingsworth.

Levin, director of the Integrated Geospatial Technology master’s program at Michigan Tech, is a certified photogrammetrist with research and teaching interests that include geodesy, photogrammetry and geospatial technologies, data, and systems.

One of Levin’s students. Erin Jean, works as a geospatial field technician for Firmatek, traveling around the country making 3D maps for mines and landfills. Jean flies drones and uses a lidar scanner to gather data. She’s earning an MS in Integrated Geospatial Technology at Michigan Tech while living on the Big Island of Hawaii, progressing toward her Michigan Tech degree with Levin serving as her faculty advisor.

“The knowledge I have learned during the course of my studies has helped me in my job both in the field and when processing the data and producing surfaces and volumetric processes,” Jean says. “This program has accelerated my career. I am now qualified and specialized for many more career paths and promotions.”

Numerous paths are available to students for exploring their geospatial passions. “Within the undergraduate degree, students can pursue the professional land surveyor path or the geoinformatics path,” says Morse. “After graduation, students can pursue cutting edge graduate certificates in UAVs and geospatial big data science.”

Michigan Tech’s ABET accredited Bachelor of Science in Geospatial Engineering offers the choice of pursuing the Professional Surveying emphasis or the Geoinformatics emphasis. The school also offers the Integrated Geospatial Technology Master of Science degree. Courses may be taken on campus or online.

Two new graduate certificates—Advanced Photogrammetry and Mapping with UAS, and Geospatial Data Science and Technology—are coming soon, as well. “These two certificates may be earned online or in person and then stacked as an alternative way of earning the Integrated Geospatial Technology Master’s Degree,” Morse says. “Students can also sign up for a single course without committing to a certificate.”

Tucked away far up in the Keweenaw Peninsula, geospatial engineering education at Michigan Tech may be one of the industry’s best kept secrets.

“The faculty of the geospatial program, Foster, Hollingsworth, and Levin, are going to change all that,” says Morse.