I’m sure some surveyors love doing construction stakeout. Even with the advent of GPS machine control and the associated modeling that goes with that type of work, there are still a lot of stakes being driven into the ground. I am one who would be happy to never pound another stake.

Some states require these types of surveys to be done by a licensed professional land surveyor, while in other states it is open to whoever can read plans and use the necessary instruments.

In the spring of 1995 I went to work for a firm that did a lot of topography surveys and some big boundary surveys. But about half of the firm’s work was construction stakeout. We were doing everything from complete site layouts on new schools to heavy highway construction layout.

There were some large residential developments, which required us to stake the new street right-of-ways with grades marked on the stakes for topsoil stripping and rough grading. After the rough grading was done, we staked the sanitary sewer, then the storm sewer and eventually curb staking.

We were so busy we could barely keep up. At one point the boss told us that we were going to be required to work 10-hour days and as many Saturdays as we could. This did not make most of us very happy. As anyone who has worked on a hot construction site can attest, it’s hard to be out there pounding stakes for eight hours let alone 10.

The pace at which we were working was perilous; not only for one’s health and sanity, but the possibility for errors loomed large. We not only had to work those long hours in the field, but the construction crew foreman was always expecting cutsheets the next day. This sometimes required us to put in extra hours in the evening.

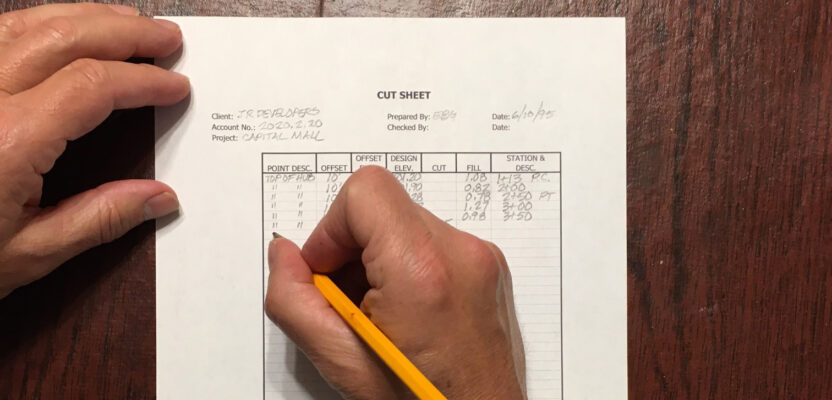

For those not familiar with the process, the cutsheets we prepared are a tabulation of the stake elevation, the proposed feature elevation (invert of pipe, top of curb, etc.) and the difference between these elevations. The difference would be expressed as a “cut” or “fill” from the top of stake. We would drive the “hub” stake (a 2-by-2 inch oak stake) flush with the ground and then set a tack for the precise point, usually offset to a feature. That top-of-stake elevation would get recorded so that even if the “guard” stake was knocked out, the grade could be measured from the top of hub.

On a very hot June afternoon I had staked some concrete curbing on one particular project, which included the expansion of a shopping mall, with the associated curbing, paving, etc. As usual, the foreman asked if he could get cutsheets the following morning. I sighed and said, “Yes,” knowing that I would be doing them on the dining room table after coaching my son’s baseball game after work.

I used the design plans to get the proposed elevations, but didn’t consider that fact that I hadn’t shot the existing pavement at the tie-in point where the proposed curb met with the existing pavement. I did take the precaution of having my wife check the math on the cuts and fills, but she was not checking the origin of the proposed elevations. The next morning, the cut sheets were dropped off at the construction site.

A few days later I found out that the curbing was poured according to my cut sheets, but the elevation did not match well with the paving and would have to be removed. When I realized my mistake, I was upset with myself for not doing what I should have done to provide accurate grades for this. I was also upset that they poured the concrete without seeing the problem in the field, but hey, that’s why they hire a professional land surveyor to stake and mark grades.

In another interesting twist on this story, the boss went out in the field (something out of the ordinary) with me a few weeks later on this same site to stake light poles. As we were finishing at 3:30 that afternoon, I reminded him that we would need to work until 5:30 in the evening to get the full mandatory 10 hours. He said, “It’s too damned hot out here to work that many hours in the field! I’m going to rescind that order to work 10-hour days.”

I think we can take two lessons from this story. First, it’s easy to make mistakes when you work too many hours, especially when you’re physically drained. Perhaps more importantly, it’s easy to make demands on field personnel when you spend a lot of your time in an air-conditioned office.