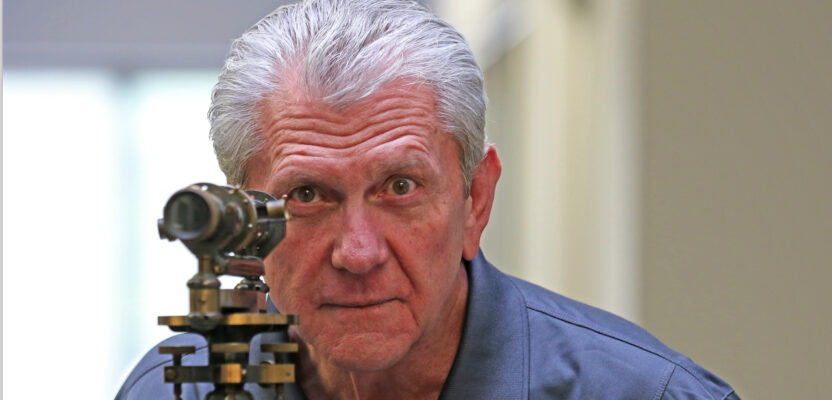

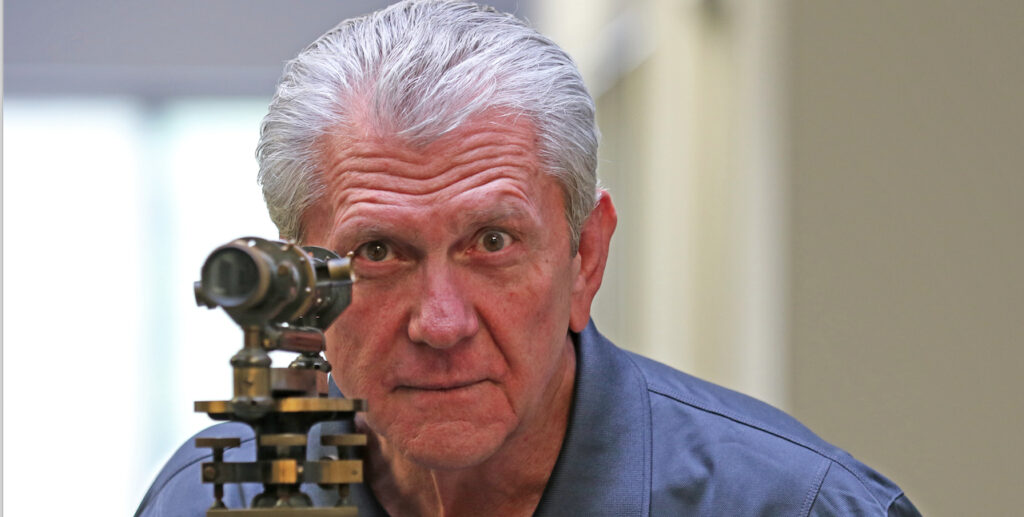

Questions and answers with retiring NSPS Executive Director Curtis Sumner

Curtis Sumner has had a venerable career in surveying, starting as an 18-year-old straight out of high school and finishing as the long-time executive director of the National Society of Professional Surveyors (NSPS). Raised in the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains of southwestern Virginia, Sumner gained on-the-job experience with the Virginia Department of Transportation before earning a degree from Virginia Tech.

After a variety of survey-related jobs, he started his own successful company, Sumner Consulting, in 1992. For about 10 years, he represented the Virginia Association of Surveyors (VAS) in NSPS, then a member organization of the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping (ACSM), and at the end of his term as NSPS president in 1998 he accepted a temporary position as executive director of ACSM.

After a variety of survey-related jobs, he started his own successful company, Sumner Consulting, in 1992. For about 10 years, he represented the Virginia Association of Surveyors (VAS) in NSPS, then a member organization of the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping (ACSM), and at the end of his term as NSPS president in 1998 he accepted a temporary position as executive director of ACSM.

The temporary position became permanent and when NSPS became a separate entity in 2012, he continued as executive director. Over the past 23 years, Sumner has diligently represented the interests of the U.S. professional surveying community in interactions with state surveying societies, governmental agencies, state and national legislators, and other national and international professional societies. With retirement on the near horizon, he will be returning to his hometown of Hillsville to be near his extended family, including two great-grandchildren.

How did you choose surveying as a career?

I grew up a minister’s son in the small town of Hillsville, Virginia. Growing up I was always working—paper route, odd jobs for my neighbors, mowing lawns, driving people to church —just whatever needed to be done. After high school I didn’t have the means to go to college, so my father brought home an application for a job with the Virginia Department of Highways (now the Virginia Department of Transportation). The day after I graduated in 1966, I went to work for a survey crew working on numerous projects, including preliminary grade staking to build Interstate 77 in the mountains near home. After three years, and having started a family, I realized I would need more education if I was going to advance in the profession, so I attended a community college and Virginia Tech, held a number of surveying-related jobs, and eventually started a surveying business. During that time, I became involved in VAS and NSPS. I’ve been on the surveying path for the past 55 years and have enjoyed every day.

Who were your mentors along the way?

My primary mentors in life were my mom and dad. They taught me the importance of how one should interact with other people—meaning the manner in which you interact with people shouldn’t have anything to do with their station in life nor where they come from. That’s probably the most valuable lesson I ever learned. It drives my approach to everything, whether it’s this job or simply talking to someone.

From a mentor perspective in surveying, relatively early on I got to know a gentleman who was a local surveyor in the area around Blacksburg, Virginia. He, more than anybody, taught me what it meant to actually be a surveyor. The phrase I always use to describe surveyors is “we solve the parcel puzzle.” Because land is like a puzzle, right? Every piece has to fit with the pieces around it, regardless of shape. He taught me the importance of finding all the information needed to solve the puzzle, and not taking anything for granted, because sometimes what you find may not be correct (although precisely measured). That lesson always stuck with me. I learned from my parents the importance of respecting everyone, and my mindset about everything surveying related was from him. Whatever successes I may have had, especially here at NSPS as a leader in the organization, are because of them.

What is your favorite part of surveying?

Surveying has been more rewarding than anything else I might have done because I feel like I’m helping people do things they can’t do for themselves. I love the research part, just piecing things together, figuring out how they’re supposed to work. The variety of the surveying profession is intriguing because you’re dealing with clients, the public in general, government agencies, and other professionals. You might be providing information for building design and construction, a boundary dispute, or many other situations. I don’t ever remember having a dull day—there’s always another challenge.

I feel fortunate to have been involved in the leadership of NSPS which has provided the opportunity to interact with people from everywhere. I’ve been able to travel to every state in the U.S., as well as a good part of the world, doing work on behalf of the surveying profession. It has been quite a ride.

I feel fortunate to have been involved in the leadership of NSPS which has provided the opportunity to interact with people from everywhere. I’ve been able to travel to every state in the U.S., as well as a good part of the world, doing work on behalf of the surveying profession. It has been quite a ride.

What have your years at NSPS taught you about working with people?

It has reinforced the importance of respecting people as individuals and accepting the fact that other people have opinions that may not agree with yours. You still have to be sensitive to what they believe and not dismiss them simply because you think you know more about an issue.

Why was NSPS formed and what role does it play in professional surveying?

NSPS history dates back to 1941 when it was the Property Surveys Division within the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping (ACSM). Over time, the number of ACSM members who were surveyors increased to the point that it made sense to form a separate organization, the National Society of Professional Surveyors. Each state also has its own society, as does the District of Columbia.

When NSPS eventually became an independent organization, we already knew that we couldn’t survive without the support of the surveying societies in the respective states, not only economically, but also in terms of enhancing our influence. We negotiated a joint membership agreement with all but a couple of the states. The benefits include lower costs to members with a combined state/national membership fee, as well as NSPS being recognized as speaking for the profession as a whole when necessary. Our membership went from a few thousand surveyors across the country to more than 15,000 members today.

NSPS is recognized as their representative in the broader geospatial arena, an example of which is the Coalition of Geospatial Organizations in which 13 geospatial member organizations participate. NSPS also represents the profession in addressing federal legislation and regulations, as well as direct interaction with federal agencies.

What does the NSPS Foundation do?

The foundation is a separate entity, but the people who sit on the foundation board are by and large surveyors. One primary area the foundation supports is education. They review the scholarship applications submitted for the annual NSPS scholarship program.

The foundation also administers a disaster relief fund, which is supported totally by donations. The fund was established to assist people who’ve been impacted by floods, hurricanes, or tornadoes. Whatever disaster it may be, people who are in the survey business are going to be impacted.

If a surveyor passes away, the foundation and NSPS staff assists the family in ordering a Final Point marker manufactured by Berntsen International to honor their loved one. The marker will show the person’s name and the geographic coordinates at the grave site, or some other chosen location. NSPS has arranged for all of its past presidents to receive Final Point markers.

Past NSPS Foundation Trustee David Atwell, a great mentor to me back in the day, set up the Bonnie S. Atwell Memorial Fund to honor his wife. Through the foundation, the fund provides financial assistance to licensed/registered surveyors to help with large medical expenses.

What is your take on requiring a four-year degree for surveyors compared to on-the-job training?

A plurality of the states have a degree requirement, and most of those have a four-year requirement. In a state that allows one to be licensed without a degree, it could be very difficult for anyone to gain the necessary experience for licensure in less than eight to 10 years.

Higher education can make that path shorter. When enrolled in a four-year program, in general, a student can take the fundamentals exam during their senior year. The amount of experience required to get to licensure after graduation varies among the state laws. Still, the degree approach is not only quicker, it also provides the level of instruction that puts one in a position to better understand all of the information required to practice in today’s world of surveying.

I would add, though, that having a degree doesn’t ensure that one automatically has all of the skills and knowledge required to resolve boundary situations—that still requires experience and interpretation of what is written (and intended) in deed descriptions.

That said, education assists in dealing with a changing world. We’re flying drones and using laser scanners and complex computer programs. I’m on the advisory team for a couple of schools, and I’ve met young people who have graduated and started their own businesses fairly quickly. They are into everything, not limited to saying, “I’m a boundary surveyor, a construction surveyor, or a topographic surveyor.” I won’t swear they are better surveyors, because that’s in your heart, in your mind, and how you choose to conduct yourself, but they have the necessary tools.

Let’s talk about professional licensing issues—multi-state licensing specifically seems to be a hot topic.

The licensing structures that are now being challenged are not new, but maybe the transient nature of how we live in America today, such as when military families move from one state to another, has made it a bigger issue.

Many people are asking: “Why do I have to jump through all these hoops to get a license to do activities in one state when I was already licensed to do them in another state?” To me, regarding the practice of surveying, this is easy to answer. It is because requirements are often different among the state laws, as are the fundamental principles for performing “boundary surveys” in particular.

Licensing is pretty important to our community for maintaining standards. We certainly understand trying to make things easier and not onerous, but at the same time, you don’t want to undermine the underlying professional structures simply to be expeditious.

Why are procurement issues so important to the surveying community?

It is a big issue for surveyors, in general, as well as engineers, architects, and all the professional services. We fully believe that procuring professional services should be based on qualifications, not on price. This discussion often takes place when a governmental body is seeking to acquire the services of a professional surveyor, engineer, architect, etc. It also can occur in the private sector when those advising their clients about procuring the services of a surveyor approach it as a matter of cost and time, not qualifications and experience.

It is important to us that everyone, not only those who are making our laws and deciding how things are done, understand who we are and what we do. It is also important that our fellow professionals understand this. It’s all part of the advocacy, whether it’s with some governmental entity or the general public.

What is NSPS doing to promote the surveying profession to the next generation?

I believe the most effective method to promote the profession is to have all of our members involved in promoting surveying to the general public and to the next generation as an attractive career choice. It is important that we reach youngsters earlier during their lives to plant the seed.

One thing we have done for decades is support the Boy Scouts merit badge program. Surveying is one of the original badges. We have a group of members around the country who work with local scout troops, as well as a dedicated group of members who attend each of the Boy Scouts Jamborees. We have also offered to be part of the Girl Scouts program, and we participate in the annual conferences of the American School Counselors Association.

Currently, when you look at a room full of surveyors, many of them look a lot like me. For years, we have wanted to make the profession attractive to a broader group of people but struggled with where to start. One of the bright spots today is a diverse group of women and men in our Young Surveyors Network who are very dedicated to outreach, in general, and to minority groups in particular. They’ve helped us attain the broader perspective that we need.

NSPS sponsors an annual Trig-Star High School Math Competition, which highlights practical applications of mathematics and raises awareness for the surveying profession. Between 30 and 40 states participate and winners from each state can compete in our annual national competition.

The world is changing rapidly, with climate change, weather events, new technology, drones, lidar, etc. How are surveyors adapting and keeping up with it all?

Surveyors do what surveyors always do; they adapt to whatever comes their way. If it’s new technology, they’re going to figure out how to utilize the tools to get the work done, to do their job more effectively, more efficiently, and more accurately.

But we must understand that the use of new technologies to enhance our ability to gather and process data precisely does not ensure that the accurate location of an object (like a property boundary marker) has been determined. It’s easy for people to gather data—with a drone, GPS, etc.—that appears to be correct. However, the results may not be accurate. In my opinion, technology can’t help you achieve better accuracy in performing surveys unless you understand and employ the fundamental principles of surveying. Were this not true, we wouldn’t see as many “pin farms” in the vicinity of where a property corner is intended to be.

What characteristics do you think the next executive director will possess?

I think the next executive director will be a surveyor. The person will have great people skills and strong communication skills overall to be able to grasp and articulate the NSPS position on issues.

The person will not be a dictator but a team player, whether it’s with staff, with leaders in NSPS, or with members in general. Everything is a team effort, and one must have the attitude that they will work with others to get things done.

One can’t come to a job like this and say, “Okay, I’m the boss who sits here in this office and tells everyone what to do.” The executive director must have respect for everyone, be able to recognize their respective capabilities, and give them the opportunity to use those capabilities. This is true working in an office with only four people where we all have to help each other, and it is true working with our partner organizations, our members, and our leadership.