To help preserve and manage cultural heritage sites, an interdisciplinary team is using 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry to model the sites at high resolution—meeting unique challenges with innovative techniques and creating novel opportunities for surveyors.

CyArk, a nonprofit organization dedicated to digitally preserving and sharing the world’s cultural heritage, uses laser scanners to generate highly accurate 3D models of buildings and monuments around the world. It has completed nearly 100 projects, often dealing with significant technical challenges by developing new scanning techniques.

CyArk, a nonprofit organization dedicated to digitally preserving and sharing the world’s cultural heritage, uses laser scanners to generate highly accurate 3D models of buildings and monuments around the world. It has completed nearly 100 projects, often dealing with significant technical challenges by developing new scanning techniques.

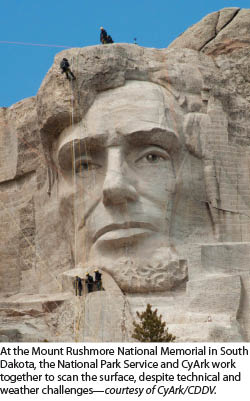

Since 2008, CyArk has had a close relationship with the Scottish government. This led to the creation of The Scottish Ten, a collaborative project to scan five UNESCO World Heritage sites in Scotland and five international heritage sites chosen by the Scottish government. So far, the team has completed work on three of the international sites: Mount Rushmore National Memorial in South Dakota, the Rani ki Vav Stepwell in India, and the Eastern Qing Tombs in China. In early April, it began scanning a fourth: the Opera House in Sydney, Australia.

CyArk’s laser scanning measurements help identify and monitor problems with the sites. They can also be used to create models and animations that help visitors understand the sites better and give them virtual access to areas they cannot see.

The Scottish Ten

Begun in 2009 and fully supported by the Scottish government, the Scottish Ten is a five-year project to create exceptionally accurate digital models of the ten sites in order to better conserve and manage them. To carry out this project and undertake other commercial ones, Historic Scotland (the Scottish heritage agency) and The Glasgow School of Art’s Digital Design Studio set up the Centre for Digital Documentation and Visualisation LLP (CDDV).

Begun in 2009 and fully supported by the Scottish government, the Scottish Ten is a five-year project to create exceptionally accurate digital models of the ten sites in order to better conserve and manage them. To carry out this project and undertake other commercial ones, Historic Scotland (the Scottish heritage agency) and The Glasgow School of Art’s Digital Design Studio set up the Centre for Digital Documentation and Visualisation LLP (CDDV).

“So far, we’ve completed the data capture phase on four of the five Scottish sites and three of the five international sites,” says Dr. Lyn Wilson, Scottish Ten and CDDV project manager at Historic Scotland. “We are working our way through the data process on each of these back in the lab in Scotland and generating outputs as we go along.”

All of the Scottish Ten sites have “unique conservation issues,” according to Justin Barton. “For example, at Mount Rushmore they are concerned with monitoring the rock blocks that make up the mountain, so providing engineering-grade information can help with that. The Rani ki Vav Stepwell in India contains hundreds of very intricately carved statues, a few feet in height, so finding a way that could record every single one of those in a high level of detail was part of the challenge,” says Wilson.

Hardware and Software

CyArk and the Scottish Ten team use time-of-flight and phase-shift laser scanners as their primary recording tools, but also adopt other methods, depending on the site. “We’ve done white light scanning of some of the key small carvings in India, we’ve done photogrammetry of some of the larger marble statues in China,” says Barton. In China, because the site is very large and, therefore, the wider landscape is also important, the Scottish Ten Team also brought in a mobile laser scanning system. For buildings that cannot be scanned up close due to their locations, it will use long-range scanners. Aerial lidar has been captured by the team for all of Scotland’s five World Heritage Sites as part of the Scottish Ten project.

To co-register the data, bring in survey information, and control all the data, CyArk and the Scottish Ten team rely mostly on Leica’s Cyclone software. The average resolution of the team’s scans is “five millimeters across the main structures,” says Barton. “Things like landscapes will be considerably less than that, of course.” Conversely, it recorded the intricate details of the small carvings on the Rani ki Vav Stepwell in India at sub-millimeter resolution.

Equipment vendors at times contribute to CyArk’s projects. In China, Barton recalls, Leica Geosystems donated much of the support equipment for the terrestrial lidar recording work, and Topcon China donated the use of one of its mobile systems. For the Sydney Opera House, CyArk and the Scottish Ten sought technical support from Maptek, which makes scanners that can scan from more than a kilometer away, and FARO, which makes a small lightweight scanner that can easily be used during rappelling down the Opera House sails.

Processing

Registration takes place immediately, on site. “At the end of every day, we download all of the data, both photographic and lidar-based, onto multiple on-site backup drives,” says Barton. “I’m there every day, registering the data. We’re tying it together and checking accuracy and data gaps to make sure that data is coming in clean and there are no errors or calibration problems. We set up additional scans as needed.”

Processing takes a long time, so it continues post-site. “Sometimes,” Barton continues, “we also photo-texture the laser scan data; other times, we photo-texture the mesh model. From there it will get cleaned up—removing extraneous data, such as birds, cars, and people. Finally, we’ll feed the dataset into a host of programs and we’ll start making meshes to create high-end visuals or a virtual environment. We can use those mesh models to create interactive environments, online as well as on mobile devices. We’ll take the data into CAD software and start creating a detailed elevation plan or elevation. We’ll work with all the site authorities to determine what, exactly, they need.”

Survey Record

For the Scottish Ten, the first and foremost deliverable is a very accurate survey record, says Wilson. “We always make sure that the point cloud is georeferenced in terms of the coordinate systems. We at Historic Scotland want to ensure that the data is useful for conservation and maintenance, particularly for sites that we manage ourselves.”

The project team includes one surveyor, as well as archaeologists, scientists, product design engineers, visualization specialists, and architects. “Everyone on the team has an understanding of surveying and several years of surveying experience in the field,” says Wilson.

Public Education and Site Promotion

In addition to assisting with preservation efforts, CyArk develops educational and interpretive materials. “We’ll create animations of the point cloud, where you fly through the site, or create cool cross-section videos to show exterior and interior spatial relationships,” says Barton. The organization has also developed software that it uses to create these virtual tours by supplementing the scan data with historic photographs and cultural information about the site and who built it.

Anyone can view a decimated version of the point cloud data via a Web browser, with a 3D viewer that CyArk developed. It allows users to access the 3D model, rotate it, take measurements, and cut sections. “We have examples of teachers who use this information to teach AutoCAD and scale models and things like that,” says Barton. Researchers may request access to the raw point cloud data. Additionally, CyArk has permission from a few of its partners to give everyone access to the data, provided it is only for educational and noncommercial use.

Some of the data from the international sites is used to help with promotion of the sites, says Wilson. “For instance, Rani ki Vav, which is on UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list, is a fantastic site but is not very well known outside of India. So, the 3D data and animations that we’ve created from the 3D models are being used there by our partners at the Archaeological Survey of India, to facilitate the UNESCO World Heritage Site bid. They will be using the materials online and locally to try to promote the site more and to attract more visitors to this place.”

Scientific Benefits

According to Wilson, who is an archaeologist, “the development of 3D laser scanning has revolutionized the way we can record archaeological sites and cultural heritage buildings. The fact that we can record so much more quickly and objectively than with traditional surveying techniques is, I think, a phenomenal advance in the field of archaeology.”

In recent years, laser scanning has been expanding very rapidly into many domains and applications. CyArk and the Scottish Ten project have been putting this technology to the service of preserving and sharing sites of great cultural significance, in the process developing new scanning techniques and expanding opportunities for surveying.

SIDEBAR 1: RUSHMORE

Mount Rushmore National Memorial

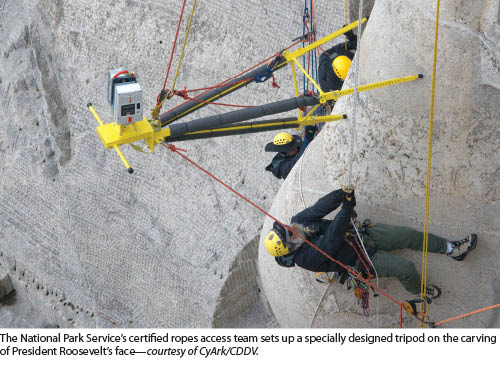

Mount Rushmore was the first Scottish Ten international site scanned, and it was “logistically challenging in every way,” recalls Justin Barton, manager of partnership development at CyArk. “Because of the engineering-level conservation needs of that site, we had to be sure to capture as much of the surface area of the carved faces as possible and as accurately as possible. We had to devise a special, customized rig system to allow the mountain-climbing ropes access team at the park to lower the scanner, on a special horizontal tripod that allowed the rotation of the scan head at multiple different angles. They had to lower that, strap a rope while they were dangling from the ropes themselves, and position it very carefully over the exact spot where we told them it needed to be.”

A team member standing on top of one of the four heads with an iPod Touch connected to WiFi turned on the scanner each time it was in position and completely stabilized. Barton registered the data on site and pointed out any missed spots.

In addition to the technical challenges, Barton recalls, South Dakota is known for extreme weather variations. “We were there in May of 2010. The first two days we were on site, our scanning was delayed because we had to wait for the snow to melt and for the stones to dry. After that, we had everything from 75 degrees, sunny, summer weather to golf-ball-size hail to tornado winds and lightning and then back to sunshine again.”

The National Park Service (NPS) wants to map the rock block sections and pieces where veins of weaker rock cut through the granite, to study in detail all the possible conservation issues. “We’ve taken that data, put it into an interactive data viewer that we built, and created tools for them to map these rock blocks and other stone fissures onto the 3D model,” says Barton.

CyArk has also been working with NPS staff to virtually capture and record in 3D, through photogrammetry, the site’s museum artifact collection. “We are developing a virtual environment of things that are no longer on site, such as the original blacksmith house, through historic recordings or documentation.” Besides the scanned images, the website includes a multimedia exhibit, textual information about the site, an interactive map, and a self-guided virtual tour,” says Bruce Weisman, manager for the memorial’s Integrated Resource Program.

SIDEBAR 2: Rani ki vav temple

Rani ki Vav Temple

The Rani ki Vav Stepwell is a deep, circular step well covered in hundreds of intricate carvings. The Scottish Ten team had to figure out how to scan it, Barton says. “We had to develop a rig that was sort of an extended arm that we were able to position on different platforms along the side of the well. [We had to be able to] extend it into the well holding the scanner cantilevered from weights and positioning it directly in the center of the well, at several different height levels. We had to use a professionally trained rope access team to stabilize the whole system and make sure that we could put it in and everybody involved was safe.”

SIDEBAR 3: The Carmel Mission

The Mission San Carlos Borroméo del Rio Carmelo, in Carmel, California, was established in 1771 and is both a state and national historic landmark. It is now undergoing a multi-year, multi-million dollar restoration and seismic retrofit. “We thought it would be a good idea to capture a 3D database of the basilica so that, in case something were to happen during the process, we would know the measurements and be able to put it back together again,” says Vic Grabrian, president & CEO of the Carmel Mission Foundation.

In particular, Grabrian explains, the basilica’s attic is a very complicated structure, above a catenary arch. “This work was done more than 70 years ago, so, there are probably no two beams up there that are the same length and at the same angle.” He brought together CyArk and Blach Construction, the general contractor for the restoration, to work together and scan the attic space. In the process, they discovered a previously unknown deflection in the roof.

The scanning also enabled them to pre-cut most of the beams. “We paired-up many of the beams in the attic, putting one beam on each side of the original beam. There were no two metal plates that were exactly the same, so they were all custom-built from the laser scanning. This saved us a lot of time and money, because we were able to have all of them pre-cut.”

SIDEBAR 4: Eastern King Tombs

The Eastern Qing Tombs, in China

A six-kilometer long processional way lined with marble statues lead to the Eastern Qing Tombs in China. “We recorded them essentially in three ways,” explains Barton. “The whole processional way with a mobile scanner, at a resolution of tens of centimeters. We went past these structures very slowly, so that we brought that down to, maybe, a few centimeters. Then, we scanned them at five millimeters or less with a Leica stationary terrestrial scanner. We also did photogrammetry around every single statue.”