How the AT was created and surveyed, from Avery’s wheel to GPS

Albert Jackman, Myron Avery, and Frank Schairer on Mount Katahdin, Maine in 1933. Credit: Appalachian Trail Conference.

The Appalachian Trail (AT) is very old, very long, and iconic. Completed in 1937, it stretches 2,189 miles through 14 states, 88 counties, 168 townships, eight national forests, six national parks, two national wildlife refuges, and more than 65 state game lands, wildlife management areas, parks, and forests. It has been called the “interstate highway” of trails, and people travel from all over the world to hike it.

The trail is still changing, with five major relocations and as many as 20 minor ones every year. Its age, size, and constant evolution make it very challenging to survey and capture in a GIS. Nevertheless, that task is mostly complete, and the National Park Service (NPS) has just released an updated, interactive online map of the entire trail.

A footpath along the Appalachian Mountains had existed since the early 1900s. In a 1921 article, Benton MacKaye—a forester, planner, and conservationist with degrees from Harvard—first proposed building a trail. Four years later, the Appalachian Trail Conference, later renamed the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), was founded to build and maintain the trail. It began work on the trail shortly thereafter and completed it by 1937.

Myron Avery—a lawyer, hiker, and explorer who at times collaborated with MacKaye and at times rivaled him—plotted out the original route, then took charge of the project and helped to complete it. “He did extensive mapping work of the official first route and wheeled the entire trail,” says Matt Robinson, a GIS specialist in the NPS’ Appalachian Trail Park Office. “That was the first official survey of the trail.”

For the first four decades, the project was entirely carried out by volunteers. When development started getting close to the trail, however, the ATC began to lobby for the federal government to take it over and make it a national trail. In 1968, Congress passed the National Trails Act, which created the Appalachian National Scenic Trail and the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail as units of the National Park System, like Yellowstone and Yosemite.

For a decade, NPS played only a very small, administrative role, because the idea was for the states to buy and hold the land. However, that didn’t work out, so, in 1978, Congress passed a set of amendments to the National Trails Act that gave NPS the authority and funding to buy land to protect it. At that point, NPS opened the Appalachian Trail Land Acquisition Office (LAO)—now the National Trails Land Resources Program Center in the Lands Resources Division—and began to identify land to buy.

Surveying the Centerline

Until NPS took it over in 1968, nobody had ever formally surveyed the trail. “Prior to that, it was just hand-shake deals with people who allowed it to go across their properties,” says Kirk Norton, the current NPS land surveyor for the AT. “It was all done by the ATC.”

To accomplish its mission, the new LAO had to map the trail—to identify where it was, what lands needed protection, which tax map parcels it covered, whether it could be re-routed if NPS acquired certain land, and so on. “A lot of planning was needed,” says Robinson, “so, they did a lot of mapping work.”

“There was no really precise map of where the whole thing was at the time,” Norton explains. “The first survey, known as the center line survey, began in 1978 and took two years. All it did was locate the center of the trail as it existed at that time, through a combination of aerial photography and on-the-ground surveys that were contracted out. As a part of that survey, inter-visible pairs of controls were set every mile, so that ground work for a conventional survey [not using any remote positioning technology] could be done to locate sections of the trail that weren’t visible through the aerial photography.”

Kirk Norton, NPS land surveyor for the AT, sets up a foresight in Pennsylvania with help from members of the Potomac Appalachian Trail club on the hill above him. Credit: Nicole Wooten.

To what extent did this work entail identifying the centerline of the trail as it existed versus creating it where it wasn’t clear or where sections were missing? “At that time, it was contiguous,” says Norton, “but a lot of it was following roads. One of the LAO’s first priorities was to get it off of roads as much as possible. So they looked at alternative routes, to get it out into the woods and as far away from roads and development as possible.”

After the surveyors had surveyed the entire centerline, realty specialists began identifying what tracks they wanted to buy. As soon as enough tracks had been bought in a contiguous area, Norton explains, the surveyors began surveying the exterior corridor boundaries of the entire corridor for the AT. “I think the oldest ones were in 1979, and the initial push to survey everything […] ended in about 2003. So, you had an ongoing survey in process that continued over 30 years, during which surveying technology changed exponentially.”

Putting the Puzzle Together

Glenn Watson, an ATC boundary technician; Pete Brown, a Potomac Appalachian Trail Club volunteer; and Kirk Norton, current NPS land surveyor for the AT, at a monument set on the survey in Pennsylvania. Credit: Nicole Wooten.

In 1977, after working for 12 years for the U.S. Geological Survey, Dave Hurst took a job with NPS in Philadelphia as a land surveyor for the AT. “They hired me, a couple of draftsmen, a secretary, and an appraiser,” he recalls. “We were the AT project.”

To try to locate the trail on the ground Hurst had to use conventional methods because GPS was not yet available (the first GPS satellite was launched the next year). He was also unable to take advantage of aerial photography, “because there was really nothing there to see,” he says. On the ground, however, the existing trail was well marked and easy to follow.

Meanwhile, volunteers were continuously moving the trail to improve it and give it more scenic views. “We had to make sure that the trail was complete and where they wanted it before we could survey it,” says Hurst. “Once we got the location of the trail down in all the states, we started collecting the deeds along this route, through each county. We also had a lot of help from the local trail clubs that would tell us the owners of the properties on which the trail was. So, we started putting together this puzzle all the way up.”

In Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina, the trail was already mostly on national lands, so it did not need to be protected. However, from the Tennessee border to Maine it was on private lands. “We wrote legal descriptions of portions of the trail that went through properties,” Hurst recalls. “We had an in-house survey crew. We also hired local surveyors to do certain properties. We started acquiring the properties and designed the corridor around the centerline. Once we got that centerline, we designed a 200-foot wide corridor that later was expanded many times over in some places.”

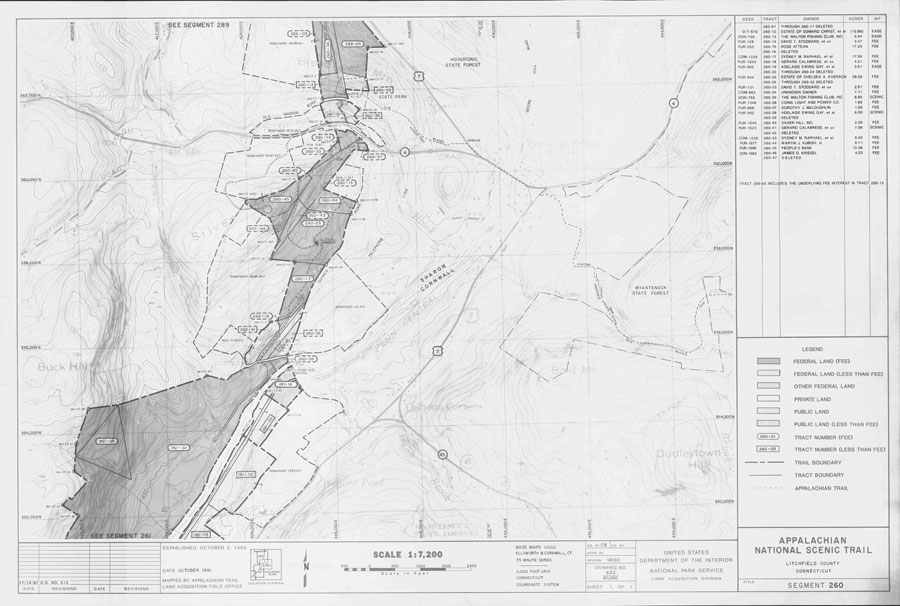

The Segment Maps

In the 1980s, the LAO made a series of unique land acquisition maps for the AT called segment maps. “There are 646 of those that cover the entire trail,” says Robinson. “The trail is placed on there and other key features—such as shelters, which are usually a point of reference for many folks—as well as some parking areas, side trails, and other things. They show all protected lands, but the emphasis was on what NPS and other federal agencies had purchased. These maps were designed as a record of what had been protected. However, because they were the most advanced thing at the time, they became the default management maps.”

Surveyor Mike Dawson determines the location of a proposed US Cellular tower near the trail in Catawba, Virginia.

Soon, the volunteer trail clubs, which work with ATC and NPS to maintain the trail, started requesting these maps and using them as field maps. “Everybody used them for 15 years. Occasionally, ATC staff and the volunteers would send in corrections and the LAO would make them.”

Too Vast for In-house

In 1984, NPS hired Chuck Sager as the second land surveyor for the AT, to work with Hurst. He stayed on the project for 20 years. Hurst and Sager’s primary duty was to act as contracting officer representatives. “We were surveyors, and we did a good amount of in-house survey work on the trail, but we contracted out at least 95% of the work because it was too vast a project to be done in-house,” he recalls.

“We had contractors in every state along the trail, from Virginia up to Maine. We would pick sections of the trail that we had acquired and were ready to be surveyed and go out and mark boundaries. Dave and I worked up contract specifications that the contractors had to follow. We’d give them copies of all the deeds and any survey plats for the properties that we had acquired, as well as any records that we had in our office; then it was their job to go out and place the monuments on the ground based on the deeds. Depending on how big the job was, the contractors had so much time to get it done.”

“Once they had done all the work,” Sager continues, “Dave and I would be the inspectors on the project. So, we would go out on the site, walk the boundaries, check monuments, make sure that they were placed correctly on the ground and stamped with the correct numbers, check the blazing on the trees at the corners—we required triple blazing on trees on the property corners—then the boundary itself, between monuments, had to be blazed. All the trees along the boundary within three feet of the boundary had to have a blaze on, and they were painted yellow. So, a big part of our job was to inspect the work that was done by the contractors.”

As lands were acquired and sections completed, Hurst and Sager hired contractors to survey the exterior boundary on both sides of the trail, then inspected their work. The monuments for the side boundaries that had been surveyed were anywhere from 300 to 1,000 feet to the side of the trail.

“The only time we ever walked the trail was probably walking in to get to the starting point, where we had to start inspecting the boundaries. In 20 years, we probably walked 1,800 miles of boundary, but not so much on the trail itself,” Sager recalls. “We were probably among the very few who ever walked around the Appalachian Trail,” Hurst echoes him.

From Theodolites to GPS

The AT surveyors started out with Wild T1 theodolites, which could measure to 3” of arc, with K&E autorangers mounted on top of them. “They were some of the first electronic distance meters to come out, back in the early 1980s,” Sager points out. “Looking back at that equipment today, it seems kind of crude, but back then it was modern stuff. It was better than having to measure distances with a steel tape or a 200-foot chain.”

This AT monument in Vermont shows the trail logo designed by Dave Hurst with the arrow pointing north for anyone who might be lost.

Later, Sager found a Topcon model, the Geodetic Total Station GTS-3C, which was much easier to use. “Those total stations had a built-in computer that would calculate the distance to horizontal, no matter at what angle you were shooting. That was a big help, too, because all survey distances are in horizontal, not vertical.”

In his earliest days working on the AT, Hurst used the TRANSIT system, GPS’ predecessor. “It mainly did the same thing but was not nearly as accurate and it took longer,” he says. “You would have to put up your antenna and let it read the satellites for 24 hours for just one point.”

In the mid-1980s, Hurst first began using GPS. “This was back when there were only three satellites in the sky and you could only work for a couple of hours at a time,” he recalls. “So we would go out and work three or four hours, go back to our motel room, then go back three or four hours later and work from daylight to dark doing that.”

“We had some Trimble units back in the 1990s,” Sager recalls, “but used them very seldom. They were good for locating big features in the field—such as the trail, water sources, lean-tos, and things like that. But they were not survey-grade. Back in those days we did not have a full GPS constellation. There were only a few satellites and often they were only available at night. We had software to figure out where they were going to be on a particular day and what was the best time of day to go out and use GPS.”

This intersection in Vermont shows a private adjoiner (red paint), the Appalachian National Scenic Trail line markings (yellow paint), as well as an AT boundary sign.

The original requirements for the exterior corridor boundaries surveys were for it to be either on state plane or on astronomic north, according to Norton, who is the son of a surveyor and was hired by NPS in 2010 to continue the work of Hurst and Sager. “Usually, the control was brought in on the ground from an NGS control nearby. You can tell from the plats that in the late 1990s and early 2000s the surveying companies were using GNSS receivers to get their control onto the trail.

“Usually, nowadays when we get a survey it is because a new parcel has been acquired or has been donated. The corridor is pretty much set. The process now is to try to widen it as much as possible, to preserve the wilderness experience and provide a buffer to the trail.”

Fond Memories

Hurst has fond memories of the hikers he met on the trail. “The average person who walks that trail is a college graduate. You see pretty sharp people out there,” he says. “Most of them said that they could not believe that we were getting paid to do that work and to be out on that trail!”

Hurst designed the trail logo used on the survey monuments, which has a spot in the middle for surveyors to use as a center point. “As the surveyors set them on the trail, we had them rotate the markers so that the arrow would point to the north,” he recalls, “so that if anybody was lost out there, if they knew this, they could find out which way was north.”

See the July issue for the second part of this article: Bringing the AT into GIS.